By Hannah-Marie Garcia, science writing intern

Think back to your early childhood science classes. Was there

ever a time you had to watch a plant grow? Your first natural sciences teacher may have used plant growth to explain basic concepts of plant biology. The process is a rewarding learning experience for students to observe their hard work pay off as those first few leaves sprout from the soil.

Walker Mill Middle School sixth-grade students and their orchid experiments.

(Credit: Hannah-Marie Garcia/SERC)

Now, imagine the work you did was part of a larger scientific project, with real-world applications. That is exactly what four sixth-grade classes are doing this year at Walker Mill Middle School. Located in a Capitol Heights neighborhood of the Prince George’s County school system, Walker Mill is one of seven schools in the Maryland area working with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) on a project called “Orchids in Classrooms.”

Inside the Classroom

Joyce Park, recently voted Walker Mill Middle School’s Teacher of the Year, is one of the sixth-grade science teachers helping engage her students in the project. In a corner of their classroom, she and her students set up two metal shelves with an assortment of polka dot watering cans and color-coded trays. For about four months, they monitored orchid seedlings growing. Students looked at how many plants were alive, measured the longest leaf, and checked to see if any new sprouts formed.

All of the orchids were grown in the same soil, but they changed the types of nutrients added: one control group (no added nutrients), one with fertilizer, and one with fungi, which orchids in the wild rely on for nutrients.

“My dad always uses fertilizer to grow our tomatoes on our porch, so I thought fertilizer would do the best,” said one female student. She, along with many other students, was in for a surprise: Over the course of the project, fertilizer didn’t seem to help the orchids grow as much as expected.

“The orchids with fertilizer did all right at first, but it turned out to be too much of a good thing,” said Alison Cawood, SERC’s citizen science coordinator, on a recent visit to the school. Too much of a good thing isn’t always the best way to get results, she explained, especially with plants as sensitive as orchids.

“Orchids live in places that no other plant wants to live, right? They live on the tops of trees and in the cracks of rocks,” Cawood said. The orchids’ unique growing pattern is one way Cawood gets the students interested in this project.

Why orchids?

Orchids aren’t easy plants to grow. In nature all orchids require a certain balance of fungi to grow and reproduce. More than half of the 200 native species of orchids found in North America are threatened or endangered. However, a challenge that researchers in labs, greenhouses, and now classrooms keep running into in conservation efforts is figuring out the best ways to propagate orchids.

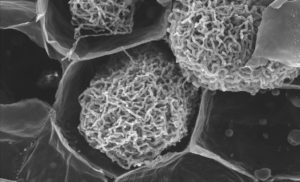

An odd couple: When fungi encounter an orchid root, the fungus roots form coiled balls called pelotons, like these, which the orchid digests for nutrients. (Credit: Liz Kabanoff, University of Western Sydney)

“It is easier to use fertilizer, because you don’t have to know what species of fungus an orchid likes or keep the fungus alive,” Cawood said. “But we don’t know what the differences in growth or survivorship might be for different species if we use fertilizer versus fungus.”

This project officially started earlier this year as part of a large-scale citizen science effort. Orchids in Classrooms aims to engage students to think beyond the walls of their classes, and look into environmental issues occurring right in their local communities. For this project, SERC partnered with the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Florida and the North American Orchid Conservation Center, a coalition of orchid-researching organizations based out of SERC. The project as a whole represents how conservation efforts often require collaboration. Challenges that occur when doing a large-scale citizen science project like this one can be improved and streamlined through feedback and experimentation.

Student to Scientist Collaboration

“It’s really cool to be working with the Smithsonian and know that what we did is going to help other real scientists,” one male student said as the project began to wrap up.

Other students described different ways they thought the project could be better, or things they wanted to know. At first, Cawood said there was some concern about how well the orchids would grow. They also weren’t sure how students would handle the data collecting. But the students here really took the project in stride.

“It’s given me a lot of ideas for other science fair projects,” said another female student in the class. She said she wants to continue looking into using different types of fertilizer, or a combination of both fungi and fertilizer, in other growing experiments.

The Future of the Project

This year, the students in all seven schools received a tropical orchid known as the pine pink orchid (Bletia purpurea). Many students wanted to take the plants home. Since the species grows naturally in Miami, Florida, this would help ensure they survive through our Maryland winters. Next year’s classes will use a more local species known as the downy rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera pubescens). Future students will then transplant their orchids around their school campuses to further encourage students to get outside and observe the world around them.

Citizen science projects like this allow scientists to gather data over a much larger scale than would be possible without the help of students and teachers. The information and inspiration gained can help orchid conservation projects and urban ecology efforts throughout the country. Here at SERC, we are excited to see what will come from something as simple as planting a seed.