by Dan Gruner

Our task this week was to begin “ground-truthing” locations on the map to evaluate them for suitability as field study sites. This was basic reconnaissance, otherwise known as exploring (or just mucking about). It’s always exciting to visit new sites. For me, recon missions recall childhood Christmas mornings, with the anticipation of finding treasure in the stacks of wrapped boxes under the tree. What treasure will we find in the marshes and mangroves?Even with the tremendous leaps we’ve gained from satellite imaging, Google Earth and other technologies, experience on the ground (or in the water) is irreplaceable. Our team must build a network of sites along the lagoons and estuaries of the Florida coast, and ultimately the globe, to understand the causes and consequences of shifts in the range of tropical mangrove species. On this day we probed several mangrove and salt marsh estuaries along the Indian River Lagoon. We tested technologies allowing real-time exploration of satellite imagery while comparing that imagery to landscape and vegetation features we saw on the ground. This was GPS on steroids! By allowing us to optimize site selection and replicate sites all along the coast, these technologies will help us characterize the vegetation of the estuaries and how they’ve changed over time.

But that day our attention was drawn away from new technology to something much older (about 50 million years old): manatees. It was a real treat to watch these massive animals splash about together within the shallow mangrove lagoons. Manatees move about within tight social groups and are never alone; we counted at least eight individuals, pups and adults. They seemed as curious as we were, coming up to the surface to observe us at close range.

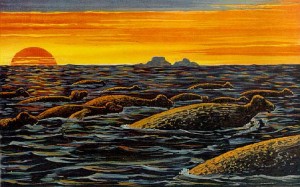

Artist's depiction of Steller's Sea Cow, printed in 1902. (Creatures of the Primitive World Series 1 and 2, illustrated by F John.)

Also driven to the brink of extirpation in Florida’s waterways, the West Indian manatee has now returned to robust population sizes thanks to the Endangered Species Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and the habitat protections and boating regulations these laws produced. These docile seagrass and mangrove herbivores are now not a rare sight in Florida’s waterways. Research suggests they provide valuable ecosystem services via their grazing and nutrient cycling, but no justification is needed to conserve them. It’s really impossible not to like manatees in their own right!

This manatee has survived a strike by a boat propeller (the white scars are visible on its back). Photo: John Parker

The manatees were a treat for us, just one more reason to investigate and explore the mangrove estuaries of Florida’s coasts.

More stories from the mangroves >>

Dan Gruner is a University of Maryland ecologist and co-investigator for the mangrove project. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number 1065098. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.