by Brooke Weigel

Brooke Weigel displays a recently-caught blue catfish in SERC’s Fish & Invertebrate Lab. (Katie Sinclair)

Have you ever wondered how far a fish can swim in one day? Acoustic telemetry enables researchers to track the movement, migration and behavior of fish. Beginning this past summer, the Fish and Invertebrate Ecology Lab started using acoustic telemetry to study the movement patterns of invasive blue catfish in the Patuxent River, a tributary of Chesapeake Bay.

Native to the Mississippi River, blue catfish were introduced for sport fishing in Virginia in the 1970s. Since introduction, these non-native top predators have expanded their range into many of Maryland’s tributaries. Their voracious appetites affect native fish populations and disrupt the food webs in these rivers. Blue catfish are the largest and most migratory species of catfish in North America. In their native waters, blue catfish have been known to migrate up to 200 km between different habitats used for spawning, feeding and overwintering. But little is known about their movement patterns within the Chesapeake Bay watershed, which is our motivation for using acoustic telemetry to track the movements of individual blue catfish.

Similar to radio tracking used to locate animals over vast distances, acoustic telemetry is a two-part system: Each fish has a transmitting tag, which emits a unique series of underwater sounds or “pings” at a random interval every one to three minutes. Stationary receivers then detect and decode these pings whenever a fish swims within range of the receiver. These detection data are converted to digital data and stored until researchers download the data onto a computer.

Interning at SERC for the past six months has given me the opportunity to be involved in every step of the process—some of which were messier than others.

Step One: Plunge into the murky depths of the Patuxent River to install the acoustic receivers. This arduous task was carried out by research technician Mike Goodison, who donned his wetsuit and goggles to perform the underwater installations. In August, we deployed an array of eight acoustic telemetry receivers spanning a 40-mile stretch of the Patuxent River.

Step Two: Catch blue catfish. Catching the catfish is accomplished using an electrofishing boat, which sends an electrical current into the water to shock fish. My job is to stand on the bow of the boat and net the fish using an unwieldy 14-foot-long net (a somewhat ridiculous-looking task).

Surgery on deck:: While Rob Aguilar makes the surgical incision, intern Brooke Weigel maintains a constant flow of anesthetic over the blue catfish’s gills. (Mike Goodison)

Step Three: Surgically insert the transmitter tags. After anesthetizing the fish using a clove oil-derived sedative, expert catfish surgeon Rob Aguilar makes the incision along the belly of the catfish and inserts the 3-centimeter-long tag. My role as catfish anesthesiologist involves maintaining a constant flow of anesthetic over the fish’s gills until Rob finishes stitching up the fish. The fish is given antibiotics to prevent infection, and a pink “spaghetti” tag for identification. The fish is placed into a recovery tank, where it starts groggily swimming around. After full recovery, the fish is released back into the Patuxent River. The implanted transmitters will last roughly two years before the batteries run out.

Step Four: Watch them swim!

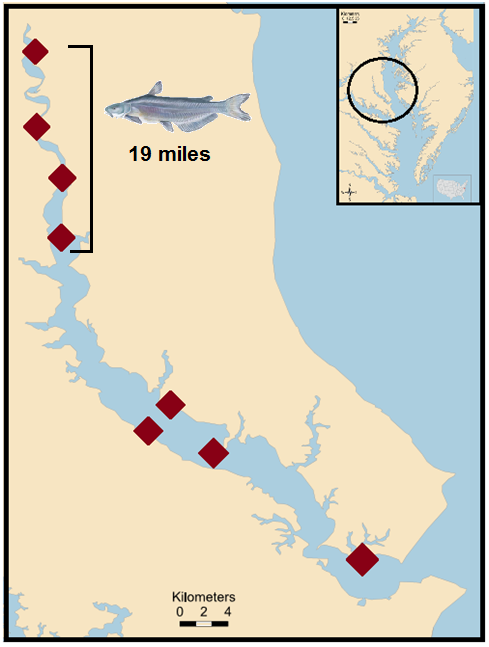

Distance Megalodon traveled in the Patuxent River over nine days. As he swam downstream, he was detected at four telemetry receivers (red diamonds).

(Brooke Weigel)

After the receivers were installed and the tags inserted into 13 catfish, there was nothing to do but wait for the fish to swim past the receivers. After downloading the first round of data from the receivers, we were excited to find that the blue catfish are moving around the Patuxent quite frequently. I was especially enthused to find that my favorite fish, named Megalodon for his hefty size of almost 12 lbs. (though he hardly tips the scale compared to the Maryland state record of 84 lbs.), had traveled 19 miles in nine days. Over a period of 50 days, Megalodon had traveled a minimum distance of 57 miles. There were three separate instances in which Megalodon moved six miles in one day. Pretty impressive for a fish!

Tracking the movements of these invasive top predators will allow us to understand more about their behavior in the Chesapeake Bay tributaries. Information about how far these fish are moving on a daily basis will complement our research on their diets. We will be able to tell whether or not the blue catfish are using different habitats throughout the day, which would affect the “snapshot” of their diet that we see when we dissect their stomachs. As we continue to tag fish in the Patuxent River, acoustic telemetry will provide us with a better understanding of the behavior of blue catfish in non-native ecosystems.