by Kristen Minogue

Parasitic slime nets attacking seagrasses. A disease that melts coral tissue down to the skeleton, whose exact cause remains unknown. If these aren’t the first places you’d look for optimism, you’re not alone.

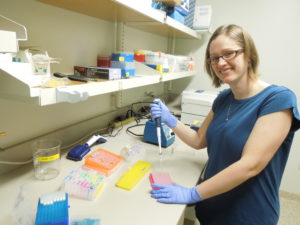

Katrina Lohan heads SERC’s Marine Disease Ecology Lab. She and postdoc Sarah Gignoux-Wolfsohn studied both ailments in Florida. They look for hope in the microscopic realm of DNA.

Katrina Lohan, head of SERC’s Marine Disease Ecology Lab, studies parasitic slime nets called Labyrinthula. (Credit: Kristen Minogue/SERC)

This January they published two papers searching for microbes infecting seagrasses and corals, using a technique called metabarcoding. Metabarcoding makes thousands of copies of one tiny DNA section. By targeting DNA common to many organisms in a sample, biologists can sequence—and if they’re lucky, identify—every organism present.

“Genetics is really cool, because it offers you a much better picture of what’s actually present,” Lohan said.

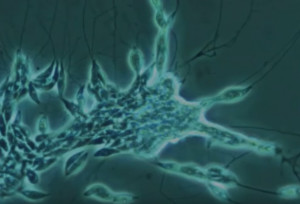

Slime net colony on eelgrass near Washington State, likely Labyrinthula zosterae, the parasite behind seagrass wasting disesase. (Dan Martin/University of South Alabama)

For seagrasses, Lohan knew exactly what to look for: a slime net called Labyrinthula. However, many Labyrinthula species exist. Not all cause seagrass wasting disease. So, Lohan tested two DNA sections to see which better identified disease-causing slime nets. The first identified a dozen slime nets, but only one was infectious. She lucked out with the second: It found only infectious ones.

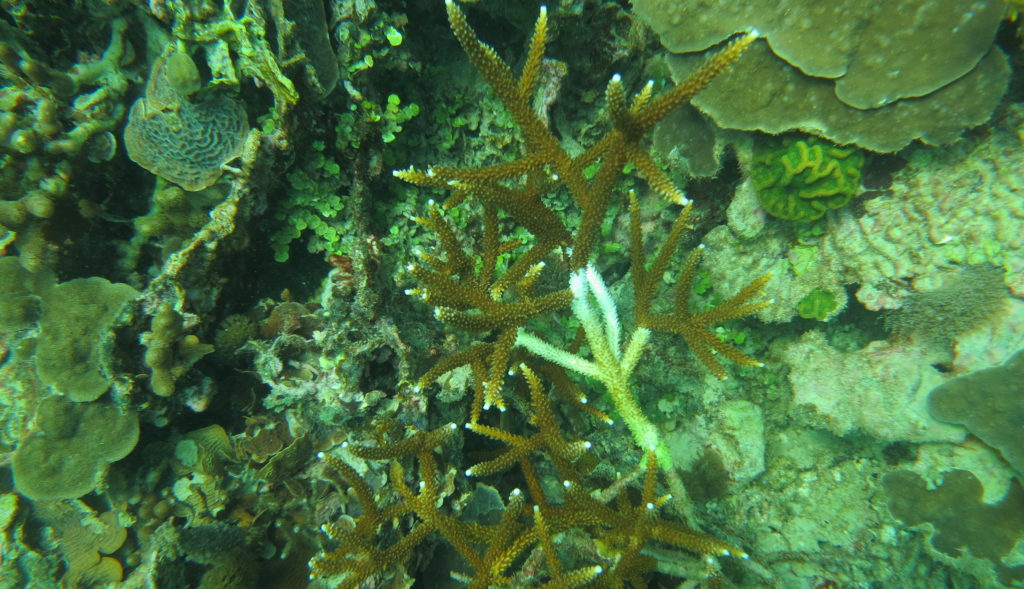

Gignoux-Wolfsohn’s task was less straightforward. She studied a 2014 outbreak of white band disease in Florida’s staghorn corals with Miami ecologist Bill Precht and three others. But no one knows exactly what causes white band disease. Her study tackled another question: What microbes keep corals healthy?

Previously, she’d noticed healthy corals in Panama generally shared one bacteria genus—Endozoicomonas. That genus was all but absent on Florida corals she sampled. Florida corals—even ones without outward disease signs—teemed with Rickettsiales bacteria. It’s possible Rickettsiales makes corals more vulnerable.

Postdoc Sarah Gignoux-Wolfsohn in Bocas del Toro, Panama. Gignoux-Wolfsohn has studied white band disease in both Panama and Florida corals. (Photo courtesy of Sarah Gignoux-Wolfsohn)

Gignoux-Wolfsohn’s study also unearthed a direct link between hotter temperatures and white band disease. Today, heat and other environmental stressors could be transforming corals down to their microbes.

“Corals in Florida are obviously dealing with a lot more stress than the corals in Panama,” she said. “They’re right next to Miami Beach.”

But knowing which bacteria make corals more resilient—and which environmental conditions boost those bacteria—could up the chances of successful restorations, she added.

For Lohan, tools like DNA metabarcoding are cause enough for optimism, even if they’re just beginning to reveal answers.

“There is this part of me that has optimism in human ingenuity, and our ability to continue to create new technologies that help us learn more,” she said.

In the meantime, their DNA work is giving them plenty of species to sift through. And if it doesn’t always reveal the species the two biologists originally set out to find, that’s just one more unexpected discovery hiding in the parasitic slime.

Keep Exploring:

Video: Nature Brain – How Many of Earth’s Creatures Are Parasites?

Q&A: Katrina Lohan, Marine Parasite Hunter

Slime Nets And Other Invasive Parasites Unmasked, Thanks to DNA

Eight Ways We Can Save The Ocean’s Oxygen

Lohan’s seagrass study, “Diversity and microhabitat associations of Labyrinthula spp. in the Indian River Lagoon System” appeared in the journalism Diseases of Aquatic Organisms No. 137, vol. 2. https://doi.org/10.3354/dao03431

Gignoux-Wolfsohn’s study, “Ecology, histopathology, and microbial ecology of a white-band disease outbreak in the threatened staghorn coral Acropora cervicornis” appeared in the journal Diseases of Aquatic Organisms No. 137, vol.3. https://doi.org/10.3354/dao03441