by Cole Johnson

Coastal wetlands are vital to our planet’s health. They store carbon, filter nitrogen and protect our shorelines. But they also can emit large pulses of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, in sudden events known as “hot moments.” These fleeting events are challenging to predict. However, understanding them is crucial in humanity’s fight against climate change.

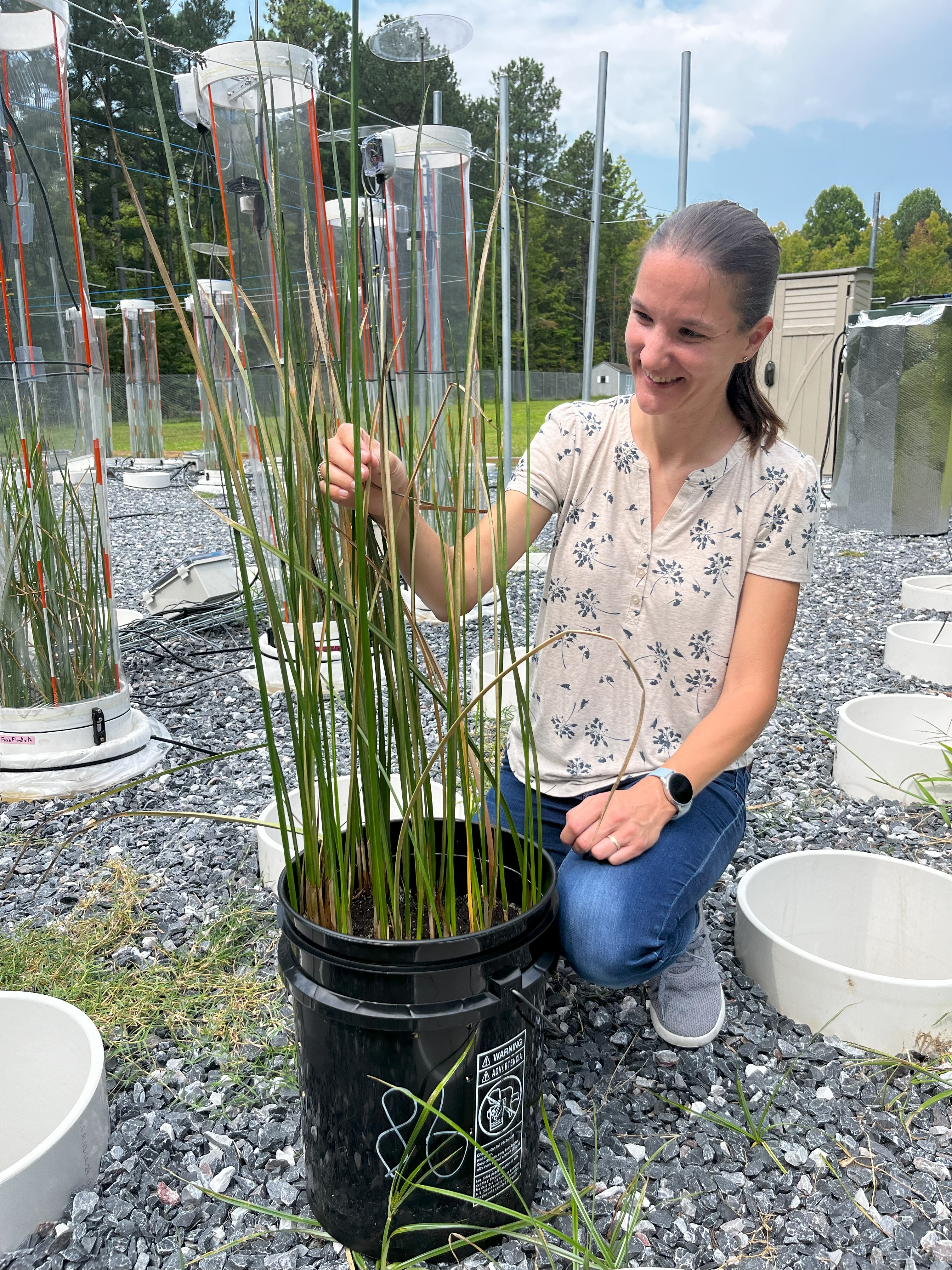

Genevieve Noyce, a senior scientist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), is leading an innovative project to better understand these hot moments in coastal wetlands.

“Coastal wetlands are incredibly resilient yet vulnerable,” Noyce said. “Our goal is to identify what causes these hot moments and how they affect greenhouse gas emissions.”

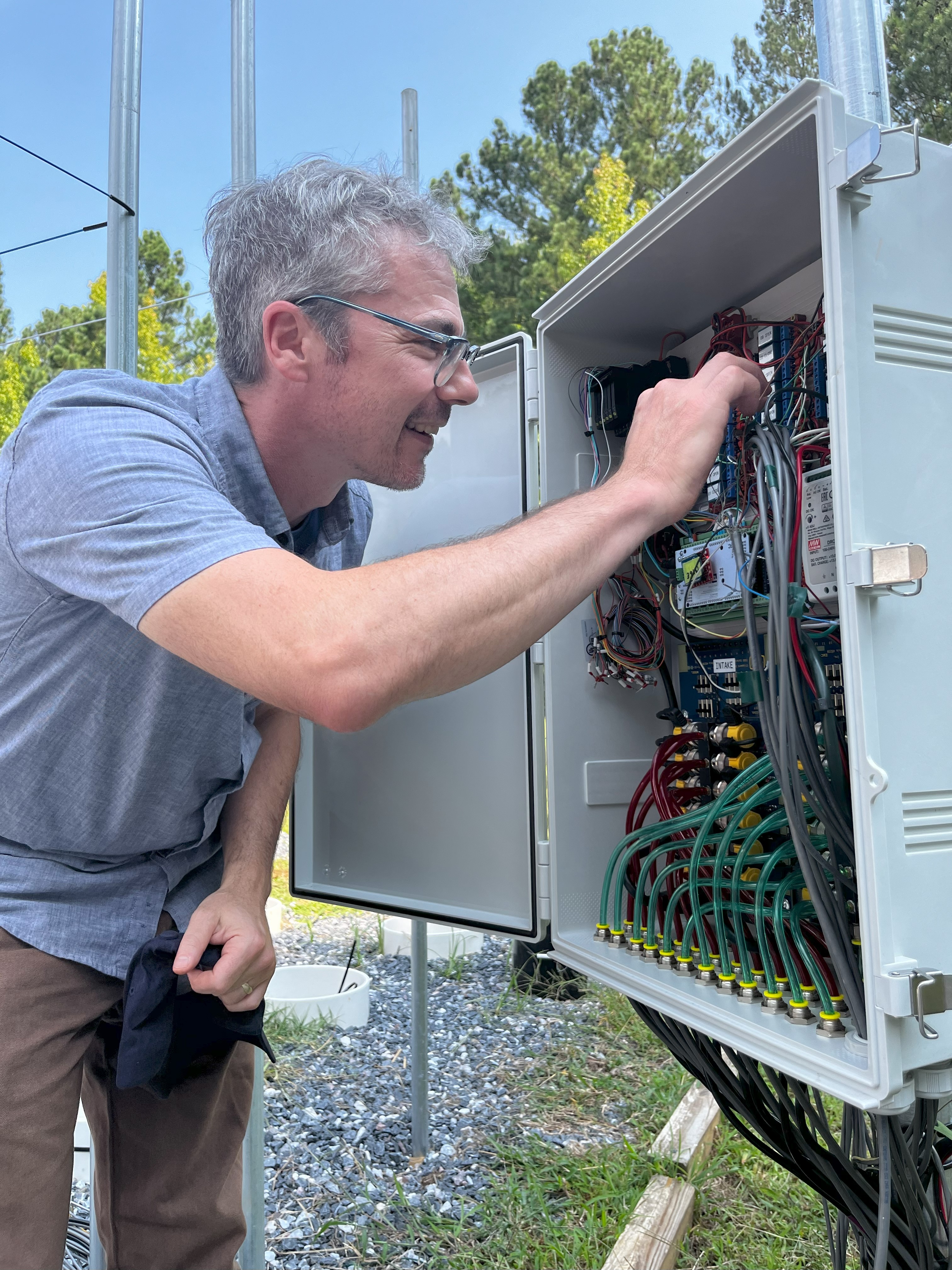

Noyce works on the project with SERC scientists Roy Rich and Alia Al-Haj. Supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and private donors, the experiment aims to uncover the triggers behind these events. They’re investigating how natural events like heat waves and flooding could generate greenhouse gas spikes. The data they collect will help us predict future hot moments and improve how they’re represented in the models we use to combat climate change.

The project lives in SERC’s experimental garden, a vast open field surrounded by trees. Inside 20 tall, open-top chambers, the scientists are growing a wetland plant called “chairmaker’s bulrush” (Schoenoplectus americanus to scientists). They chose chairmaker’s bulrush because it’s one of the most common sedges on Chesapeake wetlands. What triggers a hot moment in this plant is a good benchmark for the region’s wetlands overall.

To simulate extreme events, the team exposes the chambers to three-day pulses of heat, flooding (both saltwater and freshwater) or rapid influxes of soil nitrogen—a common side effect of fertilizer runoff. Thanks to an automated system engineered by Rich, they can then detect whether these events lead to spikes of greenhouse gases. About every 2.5 hours, each chamber seals shut for 5 minutes, recording data on carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide.

“Our automated flux chambers allow us to capture real-time data on greenhouse gas emissions,” Rich said. “These high-resolution measurements are critical for observing the rapid changes that define hot moments.”

In addition to federal funding, the project also benefits from the generosity of several donors who recognize its importance.

“I am proud to support this work,” said Paul Popick, who donated to the project with his wife, Joan Muzillo. “It’s essential to advance our understanding of these ecosystems and develop practical solutions to protect them.”

The “hot moments” experiment wrapped up its first season this year. Now Noyce, Rich and Al-Haj are busy processing the thousands of data points collected from the chambers. These data will help forecast how wetlands will respond to climate change, and how we can help them trap more carbon and emit less. The team will continue the project for another summer season and use the new mesocosm facility in the experimental garden for future research .

“The support we’ve received is enabling us to push the boundaries of ecosystem modeling,” said Rich. “It’s about more than just understanding what’s happening now; it’s about preparing for the future.”

Want to join our team and make climate experiments like this one possible? Contact Cole Johnson at JohnsonC@si.edu.