by Kristy Hill, SERC marine invasions technician

Katrina Lohan packs rubber gloves, Ziploc bags and other field essentials for a science expedition. (Kristy Hill)

The critters we’re looking for grow on coral reefs, mangrove roots, sponges, pilings, sea walls and rocks. Our goal is to collect at least 50 to 60 oysters of three or four different species from three sites along the Caribbean coast. At each site, we’ll take water quality measurements such as salinity, temperature and oxygen content. We’ll take additional notes about the oysters’ habitats, such as their distance from the shore, the depth of the water, their proximity to ports or marinas, etc. We want to obtain as much data (or information) as possible so we can better understand the environment where the oysters and their potential parasites live.

An emaciated Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Because many of the parasites that plague oysters are invisible to the naked eye, scientists need a microscope to tell for certain whether an oyster is infected. (Katrina Lohan)

Once the oysters are open, we’ll take tissue samples and preserve them for a technique called histopathology. Histopathology allows us to visually inspect the oyster tissues for parasites. The technique involves placing a cross-section of tissue containing all the major parts of the oyster in a solution that will keep the oyster and parasite cells from breaking open. We will send the preserved section to biologists who place it in wax. Having the tissue embedded in hardened wax allows us to cut very thin slices of oyster tissue with an instrument called a microtome. It’s like a super precise version of a meat slicer you’d find at a grocer’s deli counter. One thin slice is placed on a microscope slide and is stained with two different stains that help make the individual cells within the oyster tissue visible when looking under a light microscope. We’ll also be able to see parasites if the oyster is infected, and if the oyster’s immune system is responding to the presence of a parasite.

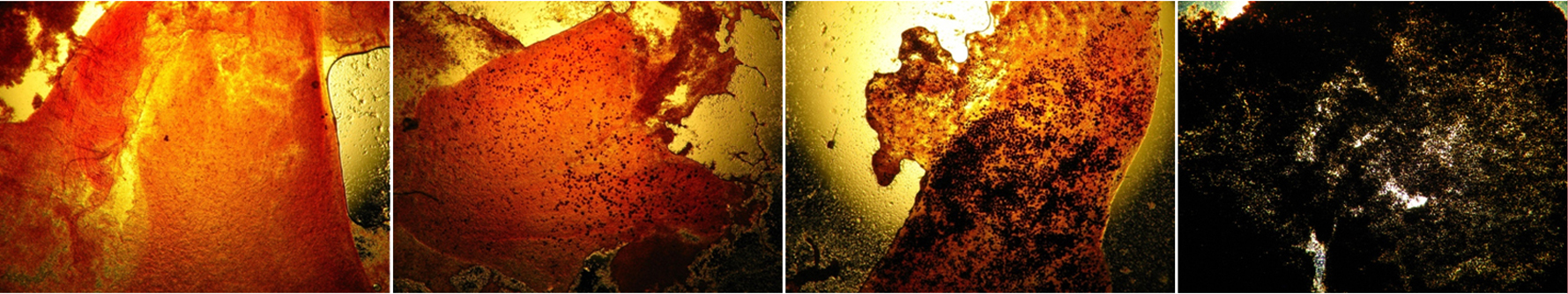

Microscopic slides of oysters at various stages of Dermo infection. In its final stages (right), the Perkinsus marinus parasite completely takes over the oyster's body. (SERC)

We will also preserve tissue for use in DNA-based methods to look for parasites. Right now, we’re making sure our tools for finding parasites are sharpened and ready to go, so we can begin our DNA lab work as soon as we return.

Lastly, we will dissect the oysters to look for bigger parasites and archive shells and tissue samples for the museum collection at the National Museum of Natural History. This ensures that future researchers will be able to use these shells and tissue samples too.

We can’t wait to see what microscopic beasties are infecting oysters and other bivalves in Panama! Very little research has been done on what parasites exist there. Most research involving oyster parasites has been prompted by the parasites causing a direct problem to commercially important species. With the changing environment, parasites will likely change, too, by altering their geographic range, possibly becoming more or less infectious. So, we’d like to see what parasites are present in Panama (and other areas that haven’t been thoroughly examined) in the case warming water temperatures allow the parasites to pack up and travel to new locations themselves.

See more postings from Panama >>

Video: STRI scientist Mark Torchin tracks marine parasites in the tropics