by Kristen Minogue

You could be forgiven if, on the long list of environmental threats, the site of an empty aquarium doesn’t fill you with dread.

Most invasive species cross our borders by accident, stuffed into crates with packing material, or clinging to the hulls or floating in the ballast of cargo ships. Often we don’t even realize they’re here until years after they arrive. But there are a few that we welcome into our homes (or fish tanks) with open arms, because they are beautiful and exotic and, well, we’re human. Sometimes they’re harmless, and sometimes our infatuation has deadly consequences.

They’re called ornamental species. They can come as pets, like the lionfish in Florida, or as aquarium decorations, like the “killer algae” that took over a large swath of the Mediterranean. California imported 11 million ornamental animals in a single year, according to a new paper co-authored by the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s Chela Zabin and her colleagues at the University of California at Davis. Inside our homes they are generally harmless. The danger comes when they escape or get released into the wilderness by their former owners. The five species below can or have caused trouble in the water, but you need only look at the Everglades to see why releasing pets into the wild anywhere is a really terrible idea.

Red Lionfish (Pterois volitans)

Status: Established

Tropical fish from the south Pacific and Indian oceans, lionfish have been present in the U.S. since the 1980s. But their invasion took off in 1992, when Hurricane Andrew smashed an aquarium in a south Florida home and sent six of them into the sea. The descendants of those six–and possibly other lionfish releases since–have fueled an invasion that has engulfed the coast of the southeastern U.S., from the Gulf of Mexico to North Carolina. They are powerful predators, able to cut the survival of native reef fish communities by up to 80 percent. As an added advantage, the venom in their spines ensures that very little preys on them.

“Killer algae”

(Caulerpa taxifolia)

Status: Eradicated

This is a cautionary tale of an invader that took six years and more than $7 million to root out. The tropical Caulerpa algae should never have been able to thrive in the temperate waters of North America and Europe. But in 1980, a new strain bred to survive in colder waters appeared in a zoo in Germany. Four years later it was released into the sea outside a museum in Monaco. Over the next decade it spread across the Mediterranean Sea, until it covered a 750-mile stretch from Mallorca to Croatia. Then, in 2000, it appeared in a California lagoon. It’s thought that an aquarium owner dumped it into a nearby storm water system. Because it spreads rapidly and smothers native seagrass—it’s been likened to carpets of Astroturf—native plants and animals suffered. In the end California managers resorted to covering the Caulerpa meadows with tarp and injecting them with chlorine. The process killed off the algae, along with most other plants and animals trapped beneath the tarp. They deemed that a lesser evil than allowing the algae to spread further, but it was a heavy price. Today it’s illegal to import the algae into the U.S. without a permit or to possess it anywhere in the state of California.

Sailfin Molly (Poecilia latipinna)

Status: Established

Sailfin Mollies rank in the top 10 ornamental imports in the U.S. Ironically, it’s the males that attract the most attention because of their vivid colors—usually blues and greens when breeding, but aquarists have developed other color varieties as well. Native to the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic, they were first brought to Hawaii in 1905 to battle mosquitoes. (They lost.) Instead, the island of Oahu saw a drop in its native damselflies. Meanwhile in California, authorities held the fish responsible for hurting the desert pupfish population.

Malaysian Trumpet Snail (Melanoides tuberculata)

Status: Established

A popular addition to aquaria, the Malaysian trumpet snail has emerged in California, Florida, Louisiana and Texas. On the island of Martinique, managers made the best of their arrival by using them to root out the parasitic blood fluke. (They won.) However, Malaysian trumpet snails have parasites of their own. They play host to the parasitic worm Centrocestus formosanus, which infects the small intestines of birds and small mammals. They’re also intermediate hosts to the parasitic lung fluke, a flatworm that can cause lung disease in humans.

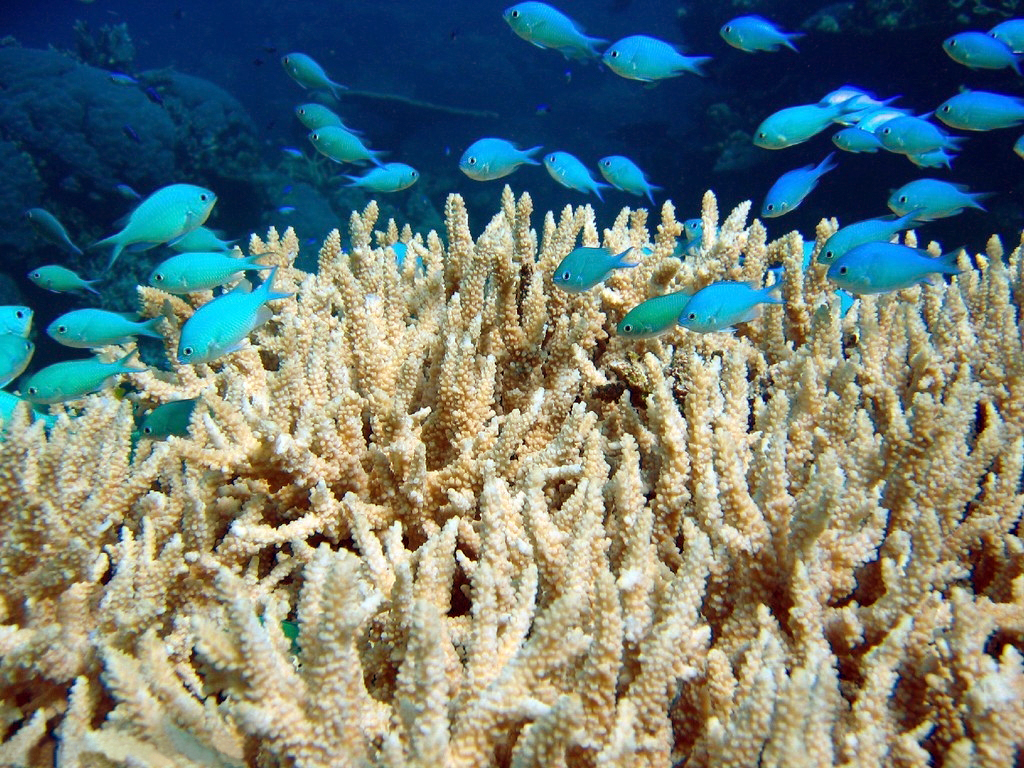

Blue-Green Damselfish (Chromis viridis)

Status: Potentially invasive

Natives of the Indo-Pacific and the Great Barrier Reef, the blue-green damselfish’s vibrant turquoise scales make it one of the most traded fish in the world. More than 800 passed through the San Francisco International Airport in just one day, according to Zabin and her colleagues. Their tolerance for colder, temperate waters give them a good chance of surviving if they ever escaped into the wild in California. The good news is that hasn’t happened yet. It’s unclear what their impact would be if it did happen—but if managers and aquarium owners are careful, we may never have to find out.

Chromis viridis photos used under Creative Commons licenses from Richard Ling and Manuel M. Almelda.