by Emily Li, science writing intern

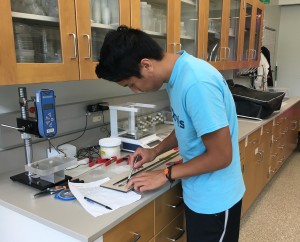

SERC intern Cole Caceres collects Japanese invasive beetles from a hormone trap for his experiment (Photo: Emily Li/SERC)

Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) intern Cole Caceres has two passions: science and cooking. He enjoys doing research and adding to the larger body of knowledge, but he hasn’t given up on owning his own restaurant. When he’s not studying nitrogen filtration as a laboratory assistant at the University of California, Davis, he’s probably watching Food Network or frying chicken wings in a sweet soy sauce glaze.

But Caceres found the perfect mix of his interests as an intern with SERC’s Terrestrial Ecology Lab. There, he cooks for invasive Japanese beetles, hoping to help shed light on their dietary preferences so that plant conservation initiatives can be more fully informed—one beetle bite at a time.

All that glitters isn’t gold

Japanese beetle on a leaf (Photo: Benny Mazur)

With their cinnamon-copper abdomens, iridescent thoraxes, and voracious appetites for more than 300 plants, Japanese beetles (Popillia japonica) are as beautiful as they are destructive. But this isn’t news—the first sighting of Japanese beetles in the United States occurred a hundred years ago in a New Jersey plant nursery in 1916.

Since then, they’ve ravaged the East Coast, leaving skeletonized leaves and fist-shaking farmers in their wakes. According to the Annual Review of Entomology, they’re the most widespread and destructive insect pest in the eastern United States, costing the turf and ornamental industry $450 million annually in management costs alone.

The question is, which plants do Japanese beetles prefer eating, and why?

Caceres is investigating if a plant’s chemicals affect its likelihood of becoming beetle food. Two schools of thought provide contradicting answers. The enemy release hypothesis suggests that invasive herbivores like the Japanese beetle excel not only because they’re free from natural enemies, but also because native plants have not evolved effective defensive chemicals against these exotic consumers. Conversely, the biotic resistance hypothesis gives native species more credit, proposing invasive herbivores don’t have the stomach for their chemicals. Caceres is determined to resolve the matter.

Please don’t kiss the chef

Intern Cole Caceres creates artificial food gels for his experiment (Photo: Emily Li/SERC)

To that end, Caceres has volunteered to act as personal chef for 500 Japanese beetles. Each insect receives two artificial food squares mixed from Caceres’ recipe of wheat germ, cellulose, anti-fungal powder, and shape-giving binders. One square is a beige control. The other experimental square has a green kick to it—the chemicals in one of 25 plants selected for the study, half of which are native. Before cutting the paste into squares, Caceres spreads it across a rectangular stencil in a pesto-like cream. Though he’s never tried the squares himself, he imagines them to have a dusty, protein-shake flavor with strong wheat notes.

“It does look delicious, sometimes,” Caceres admitted with a laugh.

When dinner is ready, the beetles receive Caceres’ all-inclusive package that includes a private culinary experience in a personal petri dish. Caceres weighs the squares before and after a 24-hour period to determine which food sample each beetle preferred. He also measures control dishes containing only food to account for any water-loss weight difference the beetle isn’t responsible for. Because the squares are nearly identical, the beetles’ eating habits will illuminate how native vs. non-native plant chemistry dictates diet: whether they prefer the control over a distasteful chemical-laced gel (think poison hemlock) or they favor the delicious chemical spices (think chili peppers). At least, that’s what Caceres thinks may be happening.

Putting the pieces together

But the lab won’t make definitive conclusions until the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama analyzes the plants used. Presently, Caceres and his fellow SERC researchers are looking to see if plant chemistry impacts what the beetles eat. In Panama, researchers will work to identify molecular differences in the chemistry between plants so SERC scientists can connect the chemical dots.

Japanese beetles in petri dishes with artificial food squares for Caceres‘ experiment (Photo: Emily Li/SERC)

“We’re doing the, ‘Oh, is it chemistry?’ question, and they’re doing beyond that—like what’s in the plant,” said Caceres.

Once they figure that out, the work isn’t over. Caceres’ research is part of a larger project studying what non-native herbivores prefer, and why. Besides Japanese beetles, the lab also analyzes dietary preferences of native white-tailed deer compared to invasive sika deer. And Caceres’ chemical focus is one piece of a bigger vegetative puzzle that could help explain what herbivores are partial to, from the hairs and thorns on leaves, to leaf size and calorie density, to phylogeny, or the evolutionary relationships between plants.

Besides cooking, these questions have become Caceres’ favorite—and least favorite—part of his internship. There’s no doubt he’s adding to the scientific understanding of invasive species, but he’s realizing how small his puzzle piece is.

“The more you know, the more you don’t know,” Caceres said. “As I’m learning more, I’m just realizing how much more there is to learn, and just being surrounded by such educated people, I have so much more work to do to get up to that level… It’s just one of those things that I’m realizing I can’t accomplish during a three-month internship—I need a lifetime.”

It looks like culinary school will have to wait.

Photo of Japanese beetle on leaf used under Creative Commons license from Benny Mazur.