Fishing, camping, and walking the dog can all have unintended consequences. (Credit: pixabay.com, 1,2,3. Used under Creative Commons CC0 license)

By Joe Dawson

Nothing seems to draw people outside like a beautiful summer weekend. A rain-free Saturday could mean taking the boat out on the water for some fishing or a family camping trip. Conservationists have found, however, that many summer activities carry the risk of spreading invasive species. A species gets the name “invasive” if it is not native to a location and causes environmental and economic damage. Here are five popular activities that can spread invaders–and tips for enjoying them safely:

Fishing

Problem: Bait Algae

A sample of wormweed that SERC scientists tested for non-native species. (Credit: Monaca Noble/SERC)

Live fishing bait itself isn’t a problem. Nobody is too worried about bait worms wriggling off hooks and taking over watering holes. However, store-bought bait can come from hundreds of miles away. Many bait worms come from New England, where they’re packed in “wormweed,” algae that keep them moist and alive for journeys on refrigerated trucks and shipped express all over the U.S. The same wormweed also harbors small creatures like juvenile shellfish, crabs, snails, and other worms that can invade new ecosystems. Wormweed can transfer mating-age adults and pregnant females, which may be especially bad for invasions.

Compared to the issue of ballast water in commercial shipping, shipping worms in algae is a small industry.

“Although this vector is relatively small compared with ballast water and hull fouling of ships, it is potent because the goal is to get baitworms to a destination in good shape,” says Whitman Miller, a marine scientist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center who has researched the potential of bait to transfer invasive species. When SERC scientists studied samples of wormweed, they found over 150 kinds of organisms, including known invaders. The wormweed packaging looks harmless enough to most anglers, so they often throw it overboard when finished with a package of worms—and unwittingly throw in potential invaders as well.

Solution: Can It

If you use store-bought baitworms preserved in wormweed for fishing, throw the unused bait and algae away in a trash can. Companies who package and ship worms could help prevent invasive species transfer by either changing packaging material or treating wormweed before they ship the worms. SERC scientists have tested a manufacturing solution to the problem, dipping the wormweed in tap water before shipping, and found that the dip eliminated 93 percent of hitchhiking species, without hurting the survival of the bait worms.

Camping

Problem: Firewood

An emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis, photographed in Occoquan Regional Park in Virginia. (Credit: Judy Gallagher, Flickr User judygva, used under Creative Commons license)

Nothing is as fun and wholesome as s’mores around a campfire, right? Maybe not. In recent decades, conservation experts studying insect invasions have identified a potent carrier: firewood. Anyone who has dealt with termites knows insects can make a home almost anywhere, and happily. Emerald ash borer and gypsy moth infestations both spread through firewood, and they can decimate forests.

“This is a really big deal,” says Leigh Greenwood, campaign manager for The Nature Conservancy’s ‘Don’t Move Firewood’ campaign. Because once new pests invade a forest, getting rid of them can be tough.

“Some species can be eradicated with fairly accessible methods, pretty cheaply. Others can only be eradicated with expensive and difficult methods, cutting down all the trees within a certain radius, for example. Other species just can’t be eradicated,” says Greenwood. Considering it can cost thousands of dollars to remove a single tree completely from a forest, eradication, where possible, can cost millions.

Solution: Buy Local

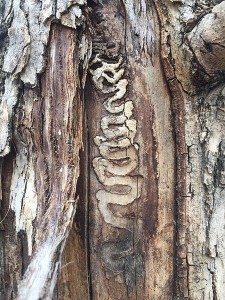

Tree damage and tunnels created by an emerald ash borer. (Credit: Judy Gallagher, flickr user judygva. Used under Creative Commons license)

Buy firewood within 50 miles of your campsite, or buy heat-treated firewood from a firewood manufacturer that kills anything living within. Check your local guidelines or hotspots of invasive activity on Dontmovefirewood.org, where they list especially vulnerable areas or places where invasive species have already been found. If you find yourself in a situation where someone has brought firewood from more than 50 miles away, burn it all to minimize the damage.

“It’s a simple change that could mean the difference between having a pest this year or not having it for twenty years,” says Greenwood.

2017 map of emerald ash borer finds and quarantine locations. (Credit: USDA)

Road Trips

Problem: Food in the Car, Pests on the Food

A non-native Oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis, laying eggs in a papaya plant. (Credit: USDA)

Taking the car to see the extended family or visit Disneyland could bring along some uninvited guests. Fruit, vegetable, and nut production are big businesses for states like California, Florida, Arizona, Louisiana, and Texas. Bringing outside produce into these states can introduce diseases and pests. While grocery store produce is subject to strict guidelines and oversight, backyard fruit and nut trees, garden vegetables, and some roadside-stand produce generally isn’t. In the summer, California works to protect itself from outside fruit flies, many of which lay eggs in cherries people bring from the Pacific Northwest. California has inspection stations along major entry points, controlling for particular fruits, veggies, and nut products throughout the year.

An Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri. These invasives feed on the sap of citrus trees and contribute to the spread of tree diseases. (Credit: Florida Dept. of Agriculture)

“We try to educate people when they come through our inspection stations,” says Duane Schnabel, the Pest Exclusion Branch chief for the California Department of Food and Agriculture. “We squish a couple cherries, put them in a cup of water, let the maggots float to the top. Some people still eat them after that.”

Packages sent between friends and family are also a major threat to local produce economies, to the point where the California Department of Food and Agriculture has deployed a team of produce-sniffing dogs to find offending packages. Not only are these packages tricky to locate, the produce is some of the most dangerous—spoiled, insect-eaten, and diseased, according to Schnabel.

Solution: Leave it at Home

When road tripping, leave the local, noncommercial fruit and nuts behind. If you try to bring produce across state lines (especially in the states listed above), know that it might be confiscated. Bringing whole trees, plants, or plant clippings is an even more efficient way to spread diseases and pests. Leave those at home, too.

Recreational Boating

Problem: Hitchhikers

A SCUBA diving researcher samples the hull of a heavily fouled recreational boat in California. (Credit: Ian Davidson/SERC)

We have known for decades that large commercial ships can carry non-native species in their ballast water tanks. Ships empty 73 million gallons of ballast water a day into U.S. harbors and can deposit invasive species along with them. Regulations and water-treatment systems have started to address the problems of ballast water-borne invasives, but small boats still pose a risk of spreading aquatic species.

In a 2014 article, SERC researchers Monaca Noble and Ian Davidson write that small boats are very important to the spread of non-native species, “…because of the varied maintenance routines, the tendency for longer port durations, and stays in a greater number of harbors, including small harbors not visited by larger commercial vessels.”

Zebra mussels (Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Small boats move from large harbors to small waterways frequently and aren’t subject to the same regulations or conditions that large boats are. This means small watercraft are big movers of aquatic species, especially those that attach themselves to the hulls of ships. The zebra mussel is one notorious invader that spreads, in part, via small watercraft. In 2009, the Center for Invasive Species Research at the University of California, Riverside, reported zebra mussels in the Great Lakes caused $500 million in damage annually.

Solution: Clean, Drain, Dry

Recreational boats are stored out of the water along Folsom Lake in California. (Credit: Vince Migliore)

Departments of Natural Resources (DNRs) nationwide have collaborated to stem the tide of aquatic species transferred by small watercraft. Certain jurisdictions have boat permits that require invasive species control, but every boat operator can do their part by cleaning any visible plant or animals from their boat before leaving a site, draining all water out of boats (bilge tanks, livewells, baitwells—anywhere water could possibly collect), and keeping boats dry and out of the water when not in use. Some aquatic animals can live out of the water for days, so DNRs recommend drying boats for five days between outings, if possible.

Walking the Dog

Problem: Sticky Seeds

Wavy-leaf basketgrass. (Credit: Vanessa Beauchamp/Towson University)

No joke, even walking the dog can spread invasive species. Scientists have identified wavy-leaf basket grass, a non-native species originating in Asia, as a possible invader, with a number of traits that could lead to its uncontrolled spread. For now, it has been spotted in a few Atlantic states but hasn’t become a major problem. Its seeds, numerous and covered with a sticky goo, can easily cling to animal fur. In tests, dogs who ran through basketgrass-containing forests picked up nearly 12,000 seeds in two minutes.

Solution: Control and Clean

Wavy-leaf seeds. Beauchamp’s team ran dogs through sections of wavy-leaf in the forest to see how much of the plant would latch onto their fur. Anwer: Too much. (Credit: Vanessa Beauchamp/Towson University)

Keep your dog on well-marked trails, clean up after them, and clean their coats before they get in the car and bring the invaders to another location.