by Kristen Minogue

A female blue crab can produce sponges like this three times a year, each with millions of eggs. But if male crabs are in short supply, she may not have enough sperm to fertilize all her eggs.

(Credit: SERC)

If you want to save a fishery, protect the females. That’s been the operating logic for decades among fishery managers, and with good reason: Females carry the next generation. Throw one mature female back, and she could produce thousands or millions more offspring. But for female blue crabs, the story isn’t always so simple.

In a study published Oct. 24, scientists from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) confirmed that a potential snag is in fact happening in Chesapeake Bay. Without enough male blue crabs to go around, some females aren’t getting enough sperm to reach their full reproductive potential. If they survive past their first year of spawning, they risk running dry.

Wanted: Fully-Charged Males

Two blue crabs mating. After mating, the male crab will often cradle the female to protect her from predators while she grows her shell back—and to prevent other males from mating with her.

(Credit: SERC)

It boils down to one inconvenient truth: Female blue crabs have an extremely short biological clock. Unlike some crab species, a female blue crab mates for just one period in her life—within a week or so after shedding her shell for the last time. During this time, she mates with one or possibly more male crabs and gets all the sperm she’ll ever receive.

“What they get during that timeframe is all they have for reproduction for the rest of their life,” said Matt Ogburn, lead author of the study.

In Chesapeake Bay, the fishery encourages harvesting more males than females. That could leave the remaining males stretched thin, he pointed out.

“If there aren’t a lot of males and there are still a lot of females that are trying to mate, then the males might mate more frequently than they’re able to rebuild their stores of sperm,” he said. “So when they mate, a female isn’t going to get as much sperm as she normally would.”

Ogburn leads SERC’s Fisheries Conservation Lab. His team began collecting female blue crabs in Chesapeake Bay six years ago. They were looking for females that had recently mated but hadn’t produced any eggs yet. They wanted to estimate how many sperm they received during mating, and compare them to crabs that had started producing broods.

In a single mating, a male crab could give a female anywhere from 770 million to 3 billion sperm. While that may seem like a lot, Ogburn’s team discovered female crabs lose up to 95% of that sperm in the next couple months, before they even have a chance to fertilize any eggs. The reason for that is still a mystery. The sperm could get lost as the sperm plug—a parting “gift” from her male partner to ensure it is his sperm she retains—breaks down. It could be those sperm were never viable in the first place.

“Or it could be something else entirely. We really don’t know yet,” Ogburn said.

Left: Matt Ogburn, head of the Fisheries Conservation Lab. Right: Technician Kim Richie prepares spermathecae (the organs where female crabs store sperm) for sperm counting. (Credit: SERC)

The team estimated it takes about four sperm to fertilize one egg. Consider that the average brood has roughly 3 million eggs, and that healthy females can produce three broods a year, and those sperm can run out pretty fast.

The good news is that even in the worst-case mating scenario, most female crabs should get enough sperm for at least one year of spawning. If they’re lucky enough to make it to a second year (only about 15% do), then things start to get more difficult.

In their field surveys, the scientists found that a female that reached her second year of spawning had, on average, 15 million sperm left. That’s enough to fertilize at least one more brood. But at three broods per year, it wouldn’t allow her to fertilize another year’s worth of eggs.

Second-Year Drought? First-World Problem

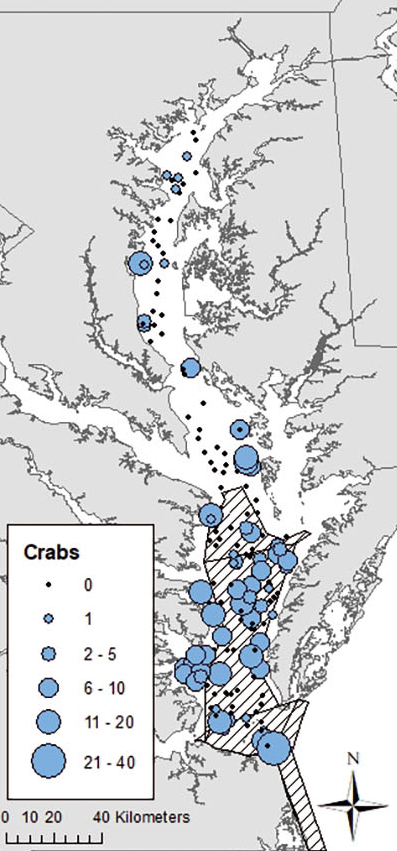

The Chesapeake summer spawning sanctuary (striped) protects females from harvesting from June to mid-September. Blue circles show where scientists found crabs during July sampling (2015-2017) for the Chesapeake Multispecies Monitoring and Assessment Program. (Credit: SERC & Marine Ecology Progress Series)

However, there’s a bigger obstacle facing female crabs in the Chesapeake. Most don’t live long enough to experience a second-year sperm drought.

Before spawning, female crabs must migrate to the saltier waters of the lower Chesapeake Bay, which provide better habitat for their larvae. A summer sanctuary in the lower Bay spans nearly 600,000 acres to protect them. Waterman aren’t permitted to take females out of that sanctuary during the peak of spawning season, from June until mid-September.

So far, the team’s evidence suggests the sanctuary is working—if females can make it there. But many get eaten or caught on the way. Virtually all the female crabs the team collected that showed signs of recent spawning were inside the sanctuary, and 98% of the crabs with eggs were at or near there as well. The team found almost no egg-bearing crabs outside of it.

According to Ogburn, many of the females caught outside the sanctuary haven’t even had the chance to reproduce once. Of those that survive the journey, the vast majority will die before their second year.

“There’s been talk in the past about protecting the migration corridors, to allow more females to get into this one sanctuary,” he said. The current management strategies have helped the crab population recover from record lows in the 1990s and 2000s, Ogburn added. Migration corridors may be an option to increase the population further or respond to future declines in the fishery.

All totaled, the team estimated sperm limitation is causing a 5 to perhaps 10% decrease in blue crabs’ reproductive output in the Bay. Ogburn said that doesn’t pose a major problem yet. It means they caught it early, and now managers can watch out for harvesting males too intensely in the future.

“There is an effect. It’s not zero,” he said.

The bigger threat to females, of course, is getting killed before they produce any offspring. For now, the ones who find themselves running out of sperm are the fortunate few.

Reference: Ogburn, M., Richie, K., Jones, M. and Hines, A. “Sperm acquisition and storage dynamics facilitate sperm limitation in the selectively harvested blue crab Callinectes sapidus.” Marine Ecology Progress Series, 629: 87-101.

DOI: 10.3354/meps13104

Learn More:

Blue Crabs Need (More Than) A Few Good Men

Thousands of Tags Could Unearth Clues to Saving Blue Crabs

Blue Crabs Come To Life In 3D