by Katrina Lohan, marine biologist

Katrina Lohan in New Zealand’s Abel Tasman National Park. (Credit: Chris Lohan)

For as long as I live, I will never forget the look on my daughter’s face the first time she saw a gorilla at the zoo. She was just over a year old and had started imitating the animal noises of those in her books, so it seemed like the perfect time to introduce her to these animals in person. Our first stop that day was the great apes. I was holding her and pointed to draw her attention to the gorilla. At first, her expression didn’t change…until the gorilla started to move toward us. The closer the gorilla got to the glass, the larger my daughter’s eyes became. She then pointed and said “monkey.” The look on her face said it all – animals weren’t just images in books that made her parents erupt with funny noises; these things were real and they moved!

That look of pure awe and wonderment is something I experience often as a scientist, because I am constantly learning new things. When you start an experiment or go out in the field to collect samples, you generally have a pretty good idea about what you are going to find (if you did the proper background research), but you never know what you are going to find. I should add that it normally takes a while to get any answers. After collecting samples, they have to be processed, which can take weeks, months or years, depending on what you want to know. The results generated have to be entered into a computer, undergo quality control, and then be analyzed. Once the analyses are complete, the real fun begins. This is when I finally get to figure out what the data are trying to tell me.

One specific example will always stay with me. As part of my postdoctoral work in the Marine Invasions Research Lab, I was attempting to find out how many different parasite species were in the ballast water of commercial cargo ships entering Chesapeake Bay. I thought there might be some, but I didn’t have a good grasp on what kinds or how many. Since many parasites can be hard to identify just by looking at them, and ballast tanks can hold a lot of water, we used a new cutting-edge method to identify the parasites by their DNA. While very cool, it can take a long time to generate the final data. Once I was finished and able to look at the identifications of all the parasites, I was stunned. There were hundreds of different parasites entering the Chesapeake inside ships.

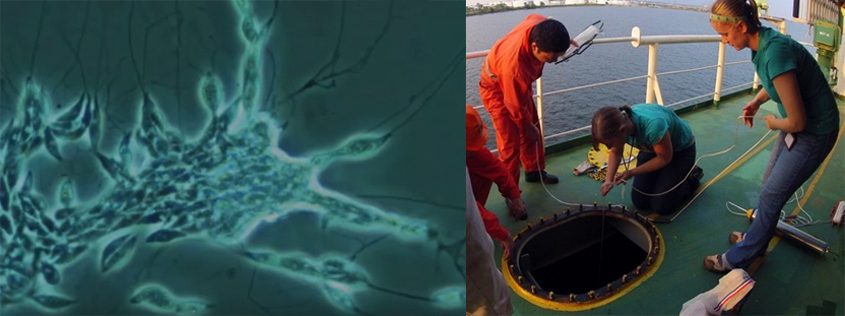

Left: Parasitic slime net, like many found in Lohan’s ship surveys (Dan Martin/Univ. South Alabama) Right: Katrina Lohan (right) and other scientists sample a ship’s ballast water to test for microscopic parasites. (Kim Holzer)

It is these times that make all the monotony in my job totally worth it – the moment when I get to learn something new. It is my favorite part about being a scientist!

Katrina Lohan is a parasite tracker and one of the newest principal investigators at SERC. She heads the Marine Disease Ecology Lab, launched in 2017, and has searched for marine parasites on both U.S. coasts, Central America and the Gulf of Mexico. This is the first of a new series of articles on the ups, downs and crazy misadventures that come with science in the real world, as told by the scientists themselves.

Read more:

Q&A: Katrina Lohan, Marine Parasite Hunter

Slime Nets and Other Invasive Parasites Unmasked, Thanks to DNA