by Carmen Ritter, SERC Fish & Invertebrate Ecology Lab intern

Picture that tiny town that one friend always tells you they’re from, with the single post office and the neighbors that know every detail of your personal life. Now picture that, on the water, even smaller. Welcome to Wachapreague, Virginia.

Wachapreague sits on the Eastern Shore of Virginia and claims to be “The Flounder Capital of the World.” The locals are some of the friendliest people you could find, and nearly everyone in the area fishes. I wasn’t there for recreational purposes, though.

This summer, I visited the Virginia Institute of Marine Science Eastern Shore Lab (VIMS ESL) with about 20 scientists from around the country to conduct a bio blitz documenting the biodiversity of Chesapeake Bay. The blitz was organized by the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and MarineGEO (the Marine Global Earth Observatory). While most scientists were from the Smithsonian and other research institutions surrounding the Chesapeake Bay, some flew in from Florida, Washington State or Puerto Rico. After gathering for a meeting on the first evening, we all prepared the lab space for samples and headed to bed. The blitz officially started first thing Monday morning.

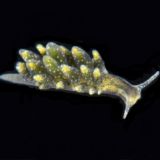

Photo Gallery: Creatures from the Wachapreague Bioblitz. (Hover over photos for more info)

At this point, I’m sure you’re beginning to wonder what a bio blitz is exactly. In short, a bio blitz is a brief period of time in which scientists attempt to collect as many unique species as possible. By gathering multiple specimens of each species, the scientists have a better chance of correctly identifying the species and collecting DNA from it. Ideally, by the end of a bio blitz, researchers will have a better idea of species variation, abundance, and biodiversity in a given area.

So how do you conduct a bio blitz? Throughout the course of the week, we usually did field work in the mornings. It could include anything from just going out to the docks to collect samples, or driving across to the Chesapeake Bay to drop in a boat and do Ponar grabs (a method for sampling animals living in soft sediments), trawls, and seines. Some teams went out to the mud flats to dig for worms and amphipods, and others explored the marsh grass for critters. Although we caught everything from squid, to crabs, to shrimp, we immediately released many of the species right back into the water; Smithsonian’s Chesapeake Bay Barcode Initiative had already collected and barcoded many larger or more common species at the VIMS Eastern Shore Laboratory. Thus, while finding some of the more charismatic creatures was fun, our collection efforts focused on the smaller critters—such as worms and amphipods—that teams had not collected in bio blitzes past.

The main lab portion of a blitz is called “barcoding.” Barcoding a species involves using a small piece of tissue from the animal to extract and replicate a piece of its DNA, giving it an identity in a scientific database that is unique to each species. The barcode initiative has a goal of collecting all of the species of Chesapeake Bay visible to the naked eye. Adding these small species helped fill a big gap in the collection.

When samples started to arrive at the lab, a conveyor belt of sorts started rolling. After we cleaned and sorted samples to identify individual species we were interested in, we passed the critters along to experts who looked at each sample under a microscope and tried to identify its exact genus and species. Some of the about 385 species collected were easy to identify. Others were more challenging, and at least 8 species might be completely new to science. Even places as well known as Chesapeake Bay have new species to discover!

These experts would in turn pass the samples to be DNA barcoded, photographed, and then preserved for future reference at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Each night, I would gather these lab photos from the day and create a slideshow of the top several critters for everyone to vote on and name a “Critter of the Day” to share on social media as part of our public outreach efforts. (You can still check them out on the MarineGEO Twitter page, @SIMarineGEO).

Amidst the organized chaos and late nights, my primary purpose was to keep the blitz from going undocumented. In the mornings, I went out on the boats and helped with field work, filming as we proceeded. The rest of the time, I photographed and filmed much of the work in and around the lab and produced a film covering the work of the bio blitz. Interacting with all the fascinating and impressive people at the bio blitz was a wonderful experience for me. I interviewed several scientists who attended the blitz to get their perspectives on what the importance of a bio blitz-type project is, as well as on some of their favorite memories and finds from the field over the years.

Overall, the bio blitz was a whirlwind experience. Being surrounded by people who are passionate about science and the ocean inspired me, and I learned so much by talking to them. The energy and excitement surrounding the field days was empowering, and constantly being outdoors is hard to beat. Though running from camera to camera and place to place was tiring, I had a great time documenting the goings-on. This bio blitz and others like it give us a more complete picture of the waters and world around us as it continues to change more rapidly than ever.