by Heather Soulen

Rob Aguilar takes photos of all DNA barcoding reference specimens they collect in the Chesapeake Bay

Rob Aguilar of SERC’s Fish and Invertebrate Ecology Lab co-authored a DNA barcoding paper this past September in the journal Environmental Biology of Fishes. Rob spoke with us about his paper and the DNA barcoding work going on in the Fish and Invertebrate Lab. While the term DNA barcoding may seem difficult to understand, it’s easiest to think about it as a uniquely identifiable species level code.

Click the sound file below to listen to the interview.

Additional barcoding details are available in the full podcast transcript.

Hello, welcome. We are with Rob Aguilar in the Fish and Invertebrate Ecology Lab at SERC, and he’s going to tell us a little bit about the new paper that he is a co-author on called the “Effectiveness of DNA barcoding for identifying piscine prey items in stomach contents of piscivorous catfish.” Welcome, Rob. Tell us a little bit about the paper you co-authored.

The paper that was just published was about using DNA barcoding to identify digested fish prey remains in the stomach contents of two non-native catfish species: the blue catfish and flathead catfish that both occur in Chesapeake Bay.

How exactly were you involved in the paper?

The main work was done by our colleagues at Virginian Tech. And we [SERC] have been doing DNA barcoding for a little while now, and they were interested in using DNA barcoding to identify the prey contents. We had talked with them as they were beginning their study, provided some guidance. We cross-validated some of their samples and we helped put the manuscript [editing] together.

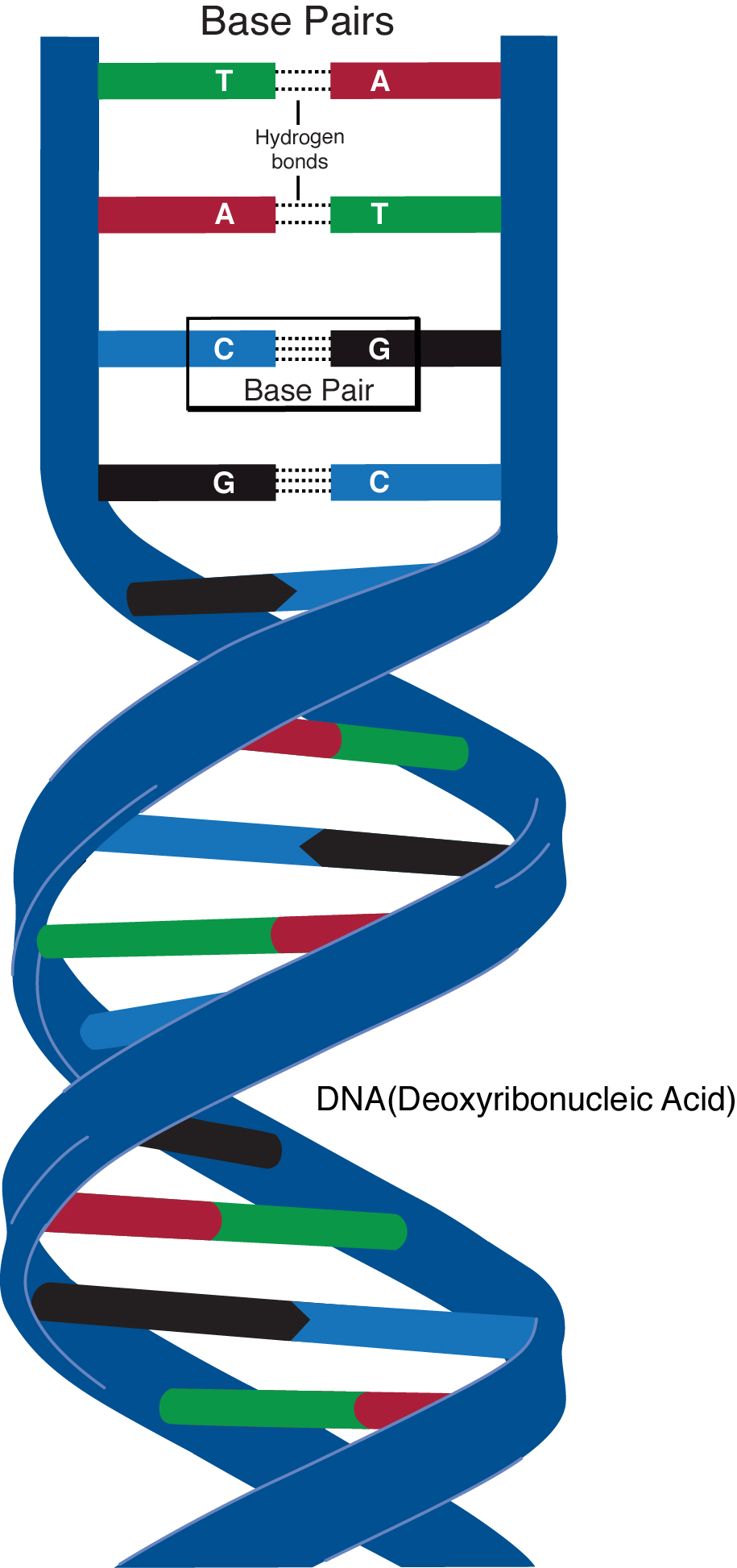

A base pair is two chemical bases bonded to one another, forming a “rung of the DNA ladder.” Photo: Darryl Leja, NHGRI public domain

And so we’re talking about DNA barcoding. What exactly is DNA barcoding in terms of this paper?

When people talk about DNA barcoding they’re talking about using a very short sequence of genetic code, a couple hundred base pairs. Then, they can use that sequence essentially as a barcode. So in theory, different species will have different barcode patterns.

So kind of like an individual fingerprint for a species?

Yes, that’s the theory and it holds fairly well. So, you can run a bunch of samples, have a bunch of different species and they should have different [DNA] signatures so they should fall out. And the other neat thing about it is not only can you tell different species, but species that are more closely related will have more similar barcodes than species that are not as closely related, so you can look at some of the relationships among the species as well.

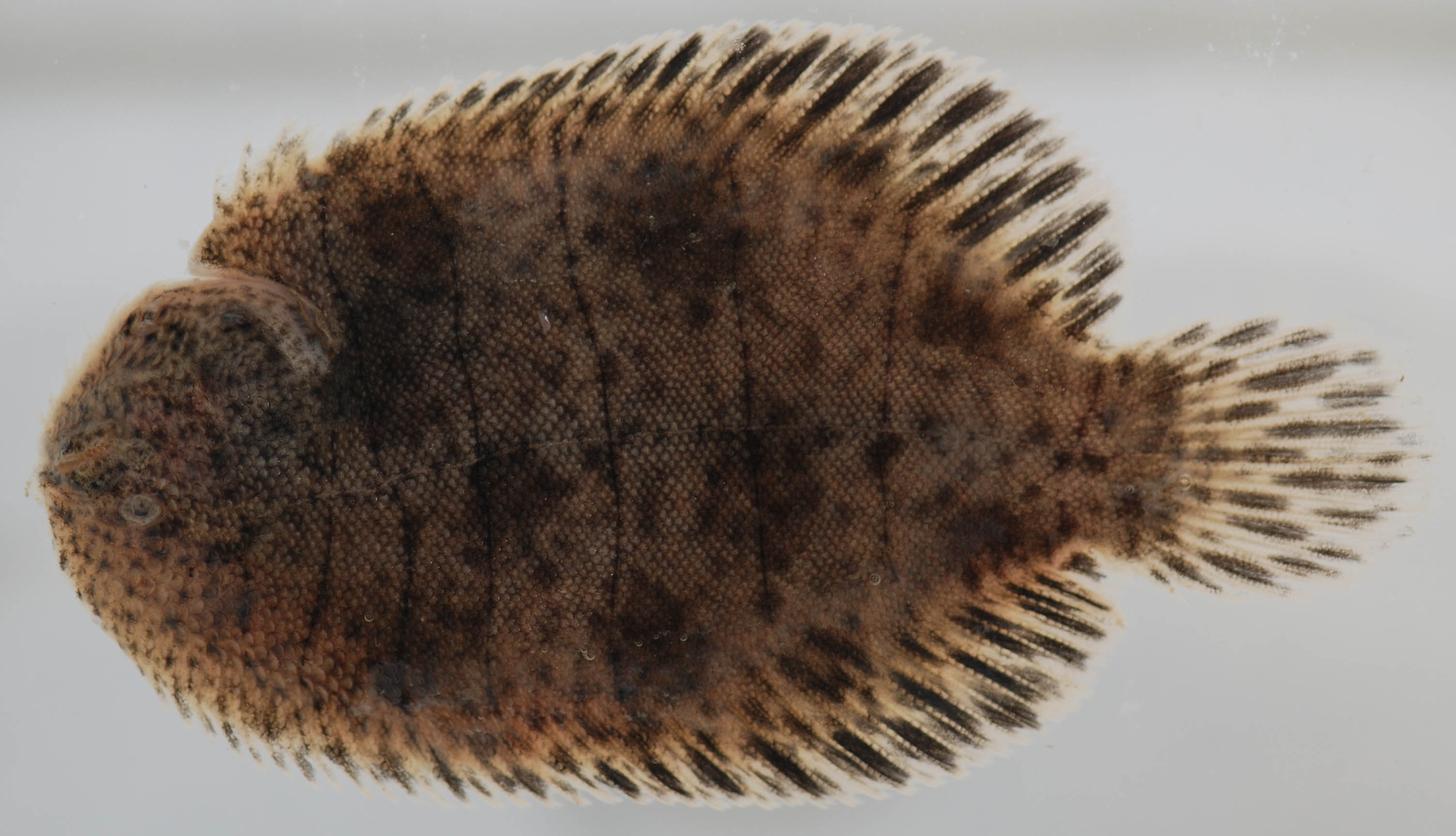

Fish in the herring family (Clupeidae) look very similar and have similar mophological features. Photo: SERC

Why was it important to do DNA barcoding as a method for this paper?

A lot of times when you look at gut contents of fish, prey items that are fish from the stomachs of other fish, they’re heavily digested. So, you aren’t able to identify what that [prey] fish species was. You can tell it was a fish. You often see just pieces of flesh and a spine and you’re like “That is a fish, but I don’t know what species that [fish] is.” Particularly as many of the species are similar morphologically, even when they’re alive and in pristine condition, so it gets really hard to tell those apart when they’re digested. And that’s a concern because some of the species we’re dealing with are of management concern. Some of the anadromous herrings, blueback herring, alewife, American shad. So there’s some interest in identifying particular prey species from the gut contents of these non-native catfish.

I know that you’re doing a little bit of DNA barcoding work here at SERC in your lab. What are the projects and what are you doing with barcoding?

We have two barcoding projects we’re doing. One is, we’re creating a complete genetic barcode library of fish and major invertebrates in Chesapeake Bay. If you’re going to identify unknown samples, you need an accurately, positively identified reference sample to match it to, because if you don’t have that than you’re not able to figure out what your unknown sample might be. We’ve been collecting fish and invertebrates, [visually] identifying them, barcoding them, uploading those [DNA] sequences into a database. Then we’re doing our own gut content barcoding work where we’re looking at the stomach contents of blue catfish, which again is non-native, channel catfish which is not native but has been established in the Chesapeake Bay for a number of years, and the native white catfish. We’re able to sequence the fish prey items from those catfish and then test them against our positively identified species that we’ve collected, and also other sequences collected by other researchers in the [DNA barcoding] databases we’re using. All the sequences that we generated from the barcoding work with the fish and invertebrates of the Bay, those are going to be publicly available so other researchers can use those.

That’s pretty cool. It sounds like a really collaborative effort that everybody can tap into and use as a resource for their own research and then also contribute back to the scientific community.

Why don’t you tell me what your favorite organisms is and why it’s your favorite organism?

My favorite organisms around here would definitely be the hogchoker.

The hogchoker? And why is that?

The hogchoker is a small, little flatfish. It’s got an awesome name and it’s got lots of personality.

It has lots of personality?

It does have lots of personality, yes.

Could you describe the hogchoker so that people can kind of visualize what a hogchoker looks like if they’ve never seen one before?

Again it’s a flatfish. It’s in the sole family. It looks somewhat like a flounder. It’s brown with some dark stripes on it. They’re cute. They suction cup to things. It’s always fun when they stick to things.

Like your hand, when you’re trying to dig it out of a net?

Yeah, your hand, in a bucket, a bin, on someone’s jacket. You know, wherever.

Because the native location and habitat for a hogchoker is someone’s jacket?

It…it happens.

Thank you very much for talking with us, Rob. Have a great one.

The Smithsonian Institution is a founding member of The Consortium for the Barcode of Life, which aims to collect DNA sequences from every species on earth.

Love the format of this blog post! Very cool. And that title = yes.