by Karen McDonald

From left: SERC home-school students Joe Giardina, Molly Enriquez and Anne Marie Nolan at the student documentary film screening. (SERC)

It began with a video series called Ecosystems on the Edge. Home-school students ages 11 to 16 came to the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center every two weeks, from September 2013 to January 2014, to create short science documentaries. Their abilities ranged from knowing how to shoot film to knowing how to turn on a computer, but full-scale video production was new to all of them. The Ecosystems series–short videos of SERC scientists working to save the coast–provided a springboard of ideas. The rest of the creative process was up to the students.

They broke into teams, ranging from one student to three. Instructor Karen McDonald walked them through the documentary-making process. Each team had to draft a proposal, draw a story board, create a shot list and script, interview SERC scientists on camera, film “B” roll (extra film) and find narrators, or read the narration themselves. Then came post-production, when the students spent weeks learning to use editing software.

By January, four teams overcame the environmental snags and technical difficulties and produced their own documentary shorts. From invasive earthworms to mute swans, here are their films:

Invisible Invasion: Joe Giardina, Molly Enriquez, Anne Marie Nolan. Using ideas from the video Earthworm Invaders, this group focused on the silent and invisible invasion of earthworms in forests and the effects of invasive worms on forest ecosystems.

Beauty and Beast: McKenna-Austin Ward, Lucy Paskoff, Max Gwinn. This documentary was inspired by the video Alien Invader, which looked at invasive barnacles in the Chesapeake Bay. For their video the students chose the invasive mute swan, and compared people’s perception of the bird as beautiful to its beastly effect on the flora and fauna of the Bay.

Behind-the-Scenes: Filming Mute Swans in the Wild >>

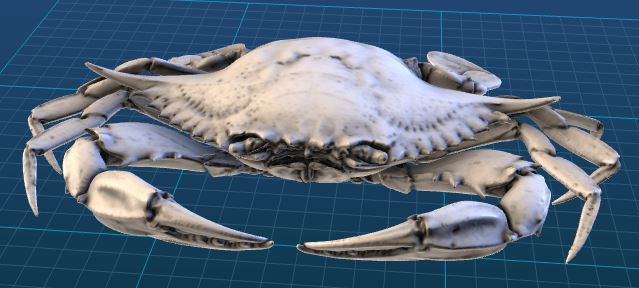

Invertebrates as Bioindicators: Xanthia Strohl. Inspired by the video Stream Health, Xanthia explored the idea of using blue crabs and crayfish as indicators of water quality and health in the Bay, and suggested ideas for helping reduce runoff.

Blue Crabs-The Soul of the Chesapeake Bay: Abbie and Katie Cannon. This team of sisters was moved by the Blue Crabs: Top Predator in Peril film. Their documentary is based on the plight of the blue crab in the Bay, and factors affecting its population and success.