by Dr. Jenny Carney

A few years ago, a massive tanker leaving lower Chesapeake Bay with a cargo of natural gas was a rare sight. Today—thanks to the booming liquefied natural gas (LNG) production on U.S. soil—they’ve become commonplace.

The U.S. is now the largest exporter of LNG globally. In July 2022, exports from all U.S. LNG facilities averaged 11.1 billion cubic feet per day. Further LNG export projects are underway in the U.S., which could expand combined daily export capacity by another 5.7 billion cubic feet daily.

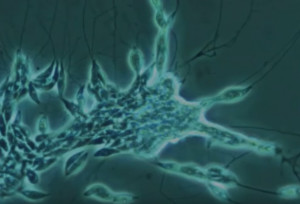

At the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), scientists in the Marine Invasions Laboratory study an underreported side effect of this trade: how shipping can transport invasive species around the globe, by picking up aquatic “hitchhikers.” In a new project, I and others in the lab are attempting to zero in on the trade’s impact in Chesapeake Bay.

Click to continue »