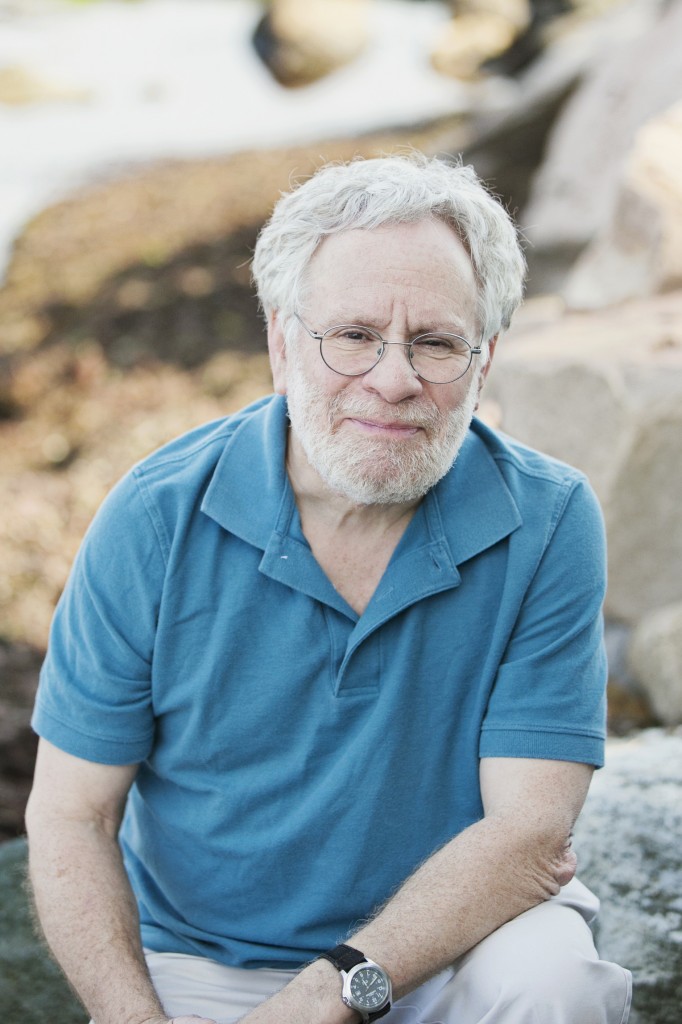

by Chris Patrick

Darin Rummel, intern in the marine invasions lab at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), raises a piece of wood twice the length of his arm and slams it onto a dock in the Patuxent River at Greenwell State Park in Hollywood, Md.

The soggy stick crumbles and a white-fingered mud crab scurries from the wreckage. Rummel adds the crab to a modest collection in a Tupperware container and raises the stick above his head again. Connor Hinton, another marine invasions lab intern, wades into a cove of muddy water in search of more crab-concealing wood. Click to continue »