SERC-West Summer Intern Spotlights

by Ryan Greene, science writing intern

Intern Elena Huynh helps clean a net during SERC’s annual zooplankton survey in San Francisco Bay. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

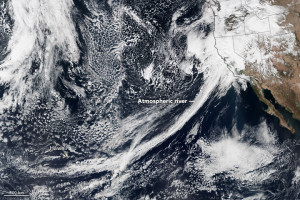

The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s (SERC) main campus is on the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. SERC’s largest West Coast outpost, SERC-West, sits on the San Francisco Bay in California. To highlight SERC’s work out west, we’ve started “Tidings from the Sunset Coast,” a summer series about the life and times of SERC-West. Our first post explored California’s wet winter. This post features the stellar interns who are spending their summer at SERC-West.

Interns at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center have the chance to work on independent projects while receiving personalized mentorship in a multidisciplinary atmosphere. Some people conduct experiments, others develop educational programs, and others (like me) write about the happenings at SERC. Simply put, SERC internships let you grow in whatever ways you want to be growing!

Check out the spotlights below to see what the interns at SERC-West are up to this summer. Click to continue »