by Kristen Minogue

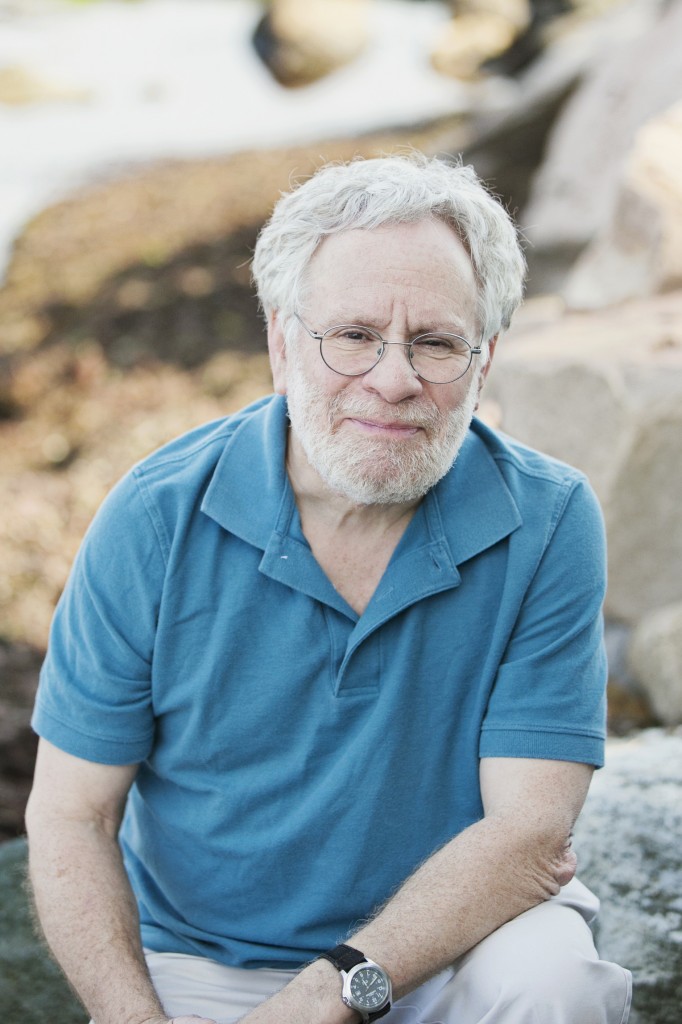

Jim Carlton tracked invasive species in the ocean for years when most scientists thought the sea was “invasion-proof.” (Anna Sawin)

There’s no official “father of marine invasions biology.” But if anyone could compete for the title, Jim Carlton, director of the Williams College – Mystic Seaport Program, would almost certainly top the list. More than 50 scientists from the U.S., Canada, Italy, Argentina and New Zealand voiced some version of that view, when they descended on the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center for a three-day symposium in April informally dubbed “Jimfest.”

Like so much in science, his career began by sheer accident. In 1962, 14-year-old Carlton stepped on a strange worm while picnicking with his family in Lake Merritt, a small lagoon near San Francisco Bay. A few weeks later he discovered the same worm in an exhibit at a local nature center. The label identified it as a tubeworm from the South Seas. “This thing in my backyard as it were, not far from my house, in this estuarine lagoon, how could this thing be from the South Seas?” Carlton remembered thinking. “So I got fascinated by that concept.”

But in the 1960s, marine invasions as a field didn’t exist. Carlton began college as a linguistics major. Only when he realized he didn’t want to be a “weekend biologist” did he switch to paleontology. Things didn’t get any easier after graduation. Carlton had a hard time selling the idea that giant cargo ships could unwittingly carry invasive species in the ballast water in their hulls. “I had a number of colleagues who thought that my studying ballast water was pretty much about as important as studying the little hard things at the end of shoelaces,” he said.

Then zebra mussels came. Once the world’s largest fossil fuel plant was forced to shut down in 1989 because mussels clogged the pipes, and 50,000 people in Michigan lost water for three days, the world began to take notice. Ballast water, in the scientific world, was suddenly sexy.

After the Great Lakes disaster, scientists uncovered invaders all over the marine world as well. “He really established the field in marine biological invasions,” said zoologist Daphne Fautin, who worked with Carlton while he was an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley. “Before his work, people thought the marine environment was invasion-proof.”

As interest grew, Carlton helped SERC bring the message of ballast water to policymakers. In 1990 he testified before Congress in favor of legislation to form the National Ballast Information Clearinghouse (NBIC), headquartered at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Today all large commercial ships entering U.S. ports are required to tell NBIC how they treat their ballast water for potential invaders.

Jim Carlton sits in front of his former postdocs, including SERC’s Greg Ruiz (second from right).

Photo: Kim Holzer

He also helped SERC marine biologist Greg Ruiz launch a database for marine invaders throughout the U.S. Christened NEMESIS (for National Exotic Marine and Estuarine Species Information System), the database has information on roughly 500 species, from algae to tunicates. “He and Greg had the idea of a database for Chesapeake Bay,” said ecologist Paul Fofonoff, SERC’s invasive species guru who does most of the literature research keeping NEMESIS up to date. “In our early meetings he sketched out a list of species that he knew about and encouraged me to find out more.”

Carlton’s work is far from over. The Panama Canal is expanding, letting even more ships through, and there’s still no consensus on the best way to purge ballast water of potential invaders. Meanwhile, his two-volume Ph.D. dissertation sits in Paul Fofonoff’s office, detailing all known introduced invertebrates along North America’s Pacific coast in 1979. It can still be a handy guide 35 years later.

Learn More

Video: How invasive species cross oceans

As Green Crabs Invade, Alaskans Launch Counteroffensive

Boaters: Beware of Hitchhikers on the Hull

From the Field: Adventures in Ballast Water Sampling on the Pacific

Sad we do not have more people like Mr. Carlton. In a day and age when global warming, climate change, (or what ever the current politically correct expression is, that describes temperature change) ballast water will create dangerous consequences in the spread of invasive s affecting Eco systems and human health. With little to no testing done to determine the different types of the thousands of temperature activated virus’s transported in ballast water, future epidemics causing human deaths could go without understanding the source. The most reprehensible policy is that of the US national broadcast media, which claims to express concern for climate change, but ignores this problem and the concerns of people like Mr. Carlton. This is going to allow the politicians to create inadequate protections that will include legislation and treaties that forever will tie our environmental regulation to the standards of the international shipping industry to protect economic globalization. Sadly they are leaving the vast majority of American people clueless about the dangers.