by Kristen Minogue

At some point, almost everyone has felt society pushing them to change. So it should come as no surprise when Nature puts the rest of the animal kingdom through the same thing. But some animals react to peer pressure in rather unusual ways. The mere presence of another animal—a friend or an enemy—can trigger an automatic and occasionally bizarre transformation. For example:

Cannibalistic Locusts

The locusts that plagued Egypt in the Exodus story may very well have started out as grasshoppers. But for most of human history people assumed these two phases were two different species. Considering the sharp contrast in their appearance and their behavior, the mistake is understandable.

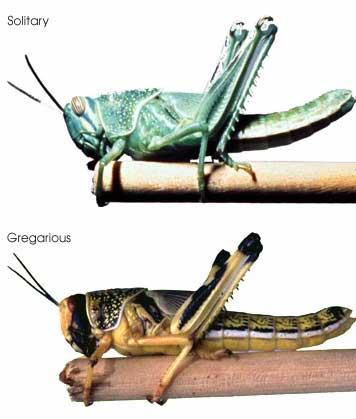

Schistocerca gregaria. Top: Solitary grasshopper phase. Bottom: Swarming locust phase. (Compton Tucker/NASA GSFC)

One of the more famous locust/grasshopper species goes by the name Schistocerca gregaria. Alone or in small groups, they live as (mostly) harmless short-horned grasshoppers. But during droughts, when vegetation grows scarce, they are forced to crowd into increasingly small spaces. The overcrowding triggers a spike in serotonin and transforms the grasshoppers into a swarm of voracious, crop-ravaging locusts. The transfiguration renders them almost unrecognizable: Their color changes from green to brown, their muscles bulge for longer flights, and their brains get 30 percent larger. They converge with other locusts to form larger bands and—sometimes—turn cannibalistic. One research team even suggested the reason swarms move with such incredible speed is because the locusts are trying to escape being devoured by their own kind.

In a 2009 experiment, scientists traced the transformation to their feet: Tickling their hind legs (as they would experience in a large swarm) could set off the Jekyll-to-Hyde transformation in as little as two hours.

Prawns’ “Leapfrog” Initiation

Giant river prawns have a strict social hierarchy. Males fall into one of three groups: At the top are the large blue-claw males—aggressive, territorial and generally dominant. Beneath them are the orange-claw males, and at the very bottom are the small males, who usually can mate only via stealth or luck. Orange-claw males can morph into blue-claw males, but only by becoming larger than the largest blue-claw male in the area. In other words, their transformation is entirely dictated by which blue-claw males happen to be nearby. Scientists haven’t yet discovered what signal sets off this leapfrog-style metamorphosis.

But the overbearing blue-claws have evolved yet another way to retain their status. Just by their presence, blue-claw males can actively suppress the growth of small males. They do not accomplish this by outcompeting them for food, or even terrifying them into losing their appetites. Small claw males eat just as much food around blue-claw males, but their bodies do not convert it into growth. It is the type of power most dictators aspire to: the power of simply walking into a room.

NEMESIS: More on the history and biology of giant river prawns >>

Gender-Switching Reef Fish

Sex changes are a common mating strategy in the fish world. In a survival-of-the-fittest race, where “fitness” generally means reproducing as much and as quickly as possible, it saves the trouble of searching or waiting for a member of the opposite sex. The transformation can work both ways.

Animals like the bluehead wrasse fish fall into the protogynous group, where a natural-born female morphs into a male. Bluehead wrasse groups generally have one dominant male with a large harem of females. If the head male dies, within minutes the largest female will begin to transform into a new “supermale.” Behavioral changes come first, as the ex-female grows steadily more aggressive. Then the ovaries turn into testes, and body color shifts from yellow to blue and green. The entire transformation takes about seven days.

Supermale bluehead wrasse. “Terminal phase” males have black and white stripes and blue-green scales. (Kevin Bryant)

On the opposite side are protandrous fish such as the clownfish, in which a male morphs into a female. Clownfish communities live in anemones, with a breeding pair and a few smaller, non-reproductive males. When the female dies, the largest male changes sex and takes on the role of the female. Meanwhile, the largest non-reproductive male will sprout sex organs and mate with the new female. Of course this means that technically the father in Finding Nemo did not have to remain a single dad…unless he never encountered another clownfish in his life.

Armor-Growing Daphnia

Tiny zooplankton like Daphnia occupy one of the lowest rungs on the food chain. As such, they’re vulnerable to attack from a wide range of predators. Some, like summer fish fry, prefer large Daphnia. Others, like copepods and insect larvae, hunt for smaller Daphnia. Evading all of them takes a certain amount of skill.

One defense Daphnia have is their ability to grow armor. When a predator approaches, their tail spine lengthens, they produce neck spines with teeth and they grow a cone-shaped helmet. But Daphnia have also evolved to think of their children. The presence of a predator can affect the way they reproduce. And fortunately for Daphnia, different predators give off different chemical signals. (At least the ones that have ingested other Daphnia in the recent past.)

When a potential predator enters the area, the mixed cocktail of crushed Daphnia, digestive juices and bacterial enzymes in its stomach sends an alarm to any living Daphnia nearby. Researchers discovered that Daphnia can tell what kind of predator is near just by the chemicals it gives off and adapt their procreation accordingly. If the predator prefers large Daphnia, they reproduce sooner and produce smaller offspring. If the predator prefers small Daphnia, they delay reproduction. When they do begin procreating, their offspring are larger.

Image of giant river prawn (Martin Eckert) used under the Creative Commons license here. Images of bluehead wrasse fish (Kevin Bryant) used under the Creative Commons license here.