by Kristen Minogue

It’s a trick worthy of any spy thriller: to elude an enemy, hide among something it won’t notice. Or, to be extra safe, something it finds incredibly disgusting. It turns out the same strategy can work for plants that don’t want to get eaten. Sometimes.

For the last seven months, intern Marina LaForgia has kept tabs on tree saplings in more than a dozen different environments and watched the game of ecological survival play out. As she tracked their progress, she searched for an answer to a deceptively simple question: Is diversity good for plants? When it comes to the food chain, will hungry herbivores pass over tasty plants if they’re surrounded by less palatable ones?

To test the idea, ecologist John Parker and his lab created dozens of experimental plots in the SERC forest. Inside, they planted 15 saplings in various combinations. Some contained only one species, such as oak or red maple or sweetgum. Others had anywhere from three to 15 different species. Some were left unguarded. Others had fences that would let in insects but keep out deer. LaForgia spent the next summer and fall observing which plots sustained the most damage.

Marina LaForgia (left) puts up an experimental forest plot with technician Jess Shue and fellow interns Kiel Edson and Jeff Miguel (right). (John Parker/SERC)

But the rules changed when insects entered the picture. Unlike deer, insects didn’t seem to care whether their food appeared on its own or was part of a mixed salad. LaForgia actually discovered the opposite was going on – on average, plants in mixtures were more likely to get eaten by insects than plants on their own. Diversity turned from an asset into a liability.

LaForgia thinks it may be matter of mobility. Larger animals like deer can afford to be pickier eaters, because they can cover more ground in search of food. But for insects, traveling twenty or thirty feet to explore another patch can be an enormous hassle. If they find a plant they like, they’re not inclined to complain about its neighbors.

For the tree saplings, diversity can become a double-edged sword. By surrounding themselves with plants that deer don’t like, vulnerable plants are safer. But the reverse can happen just as easily. By associating with plants that insects do like, plants that would otherwise be safe are suddenly at risk.

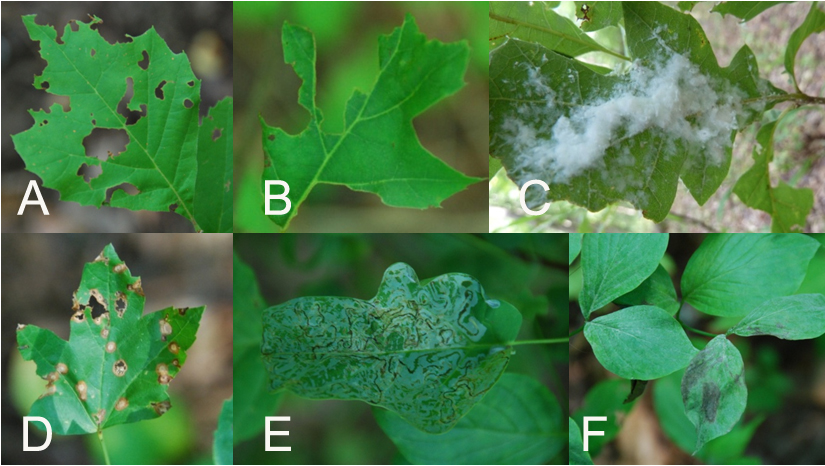

Examples of leaf damage. A) Shredding from phasmids; B) feeding by beetles or insects in the moth and butterfly family; C) mealy bug residue; D) fungal disease Anthracnose; E) dark lines from leaf miner maggots that live inside leaves and mine out nutrients; F) powdery mildew. Credit: Marina LaForgia

I find it amazing how damaged those leaves are

Luke

I love google

I have always been amazed by the power of nature, I believe that the only thing that we must do is to know it, explore it and stop destroying it!

You are absolutely right, insects just can’t afford being picky on food as they should travel twenty or sometimes thirty feet to explore another patch and it is quite a distance for them to get over. Very interesting post!

Goodness, how interesting nature can be. I am impressed.

INTERESTING work! Thanks for the post!

What a fascinating study! LaForgia’s idea makes so much sense.

White flies have been eating holes in my chile plants. The tiny buggers are difficult to see, but there damage is highly visible.

Lovely photos. It takes a great deal of panietce to get these creatures on film! (Or digital media.)There’s so much to be done to deal with the environmental stressors on pollinators. For honey bees, allowing them to have a natural cycle without transporting them from one monoculture harvest to another would be a good start. Native pollinators need to be promoted too by doing things like putting up mason bee boxes and planting pollinator gardens.