By Sarah Hansen

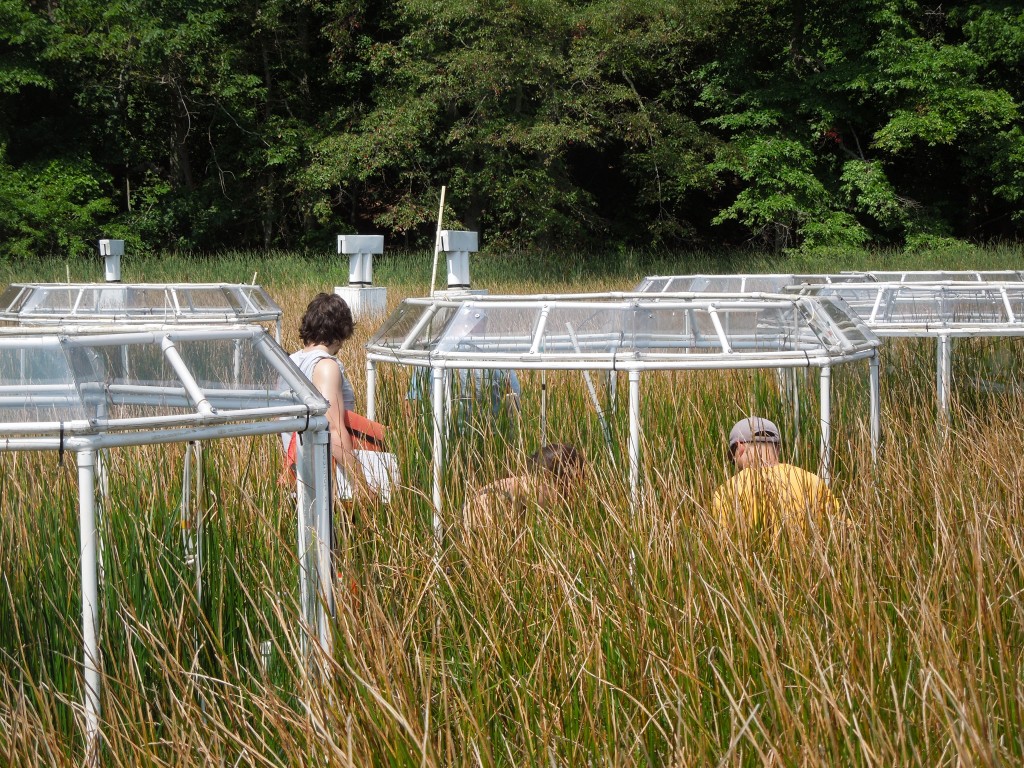

At first encounter, the marsh looks as if it came out of a Heinlein novel. Boxy white robots dot the wetland, igloo-shaped encampments litter the landscape, and thick black tubes snake across the mud—wait, did that one just move? On closer inspection, clusters of human beings appear crouched in the sedge, carefully taking measurements for the annual Global Change Research Wetland (GCREW) Summer Marshfest.

“These two weeks are the most important two weeks of the year for us,” said Smithsonian Environmental Research Center biogeochemist Patrick Megonigal. During Marshfest, senior scientists, postdocs, volunteer citizen scientists, interns, lab techs and visiting students all join forces to collect data for three experiments focused on climate change and nutrient cycling, all managed by Megonigal.

They’re collecting the data in one fell swoop at the end of July because this is when the plants are at peak biomass. Earlier in the summer they’re still growing, and later on they start to wither. This is the way it’s been done for 27 years. The oldest of the experiments began in 1987 and is still going strong. It’s important to collect the data at the same time, in the same way, each year so that comparisons between years are valid.

Citizen scientist Joseph Downey (left), grad student Rachel Gentile (center) and postdoc Meng Lu (right) collect data at GCREW.

The only thing that does change is the personnel. A different combination of workers comes out to the marsh each day. Today they’re measuring sedges growing in partially enclosed chambers two meters in diameter. For this experiment, the snake-like black tubes pump ambient air into about half the chambers and air with elevated carbon dioxide into the rest. Extra nitrogen simulates a polluted estuary, so scientists apply a liquid version to the soil surface in about half the chambers. There are three to five chambers of each type (ambient air only, elevated CO2, elevated nitrogen, or both) in a given experiment, for a total of 62 across this sprawling site.

Joseph Downey, a citizen scientist, explains that the experiment they’re working on today entails measuring four characteristics of 30 plants in each of six small areas within the chamber and two just outside the chamber. That’s 960 measurements per chamber, or 19,200 for all 20 chambers in this experiment. And that’s just the sedges. They also cut out the same number of small sections of grass and then take measurements in an on-site lab.

Downey is a student at University of Paris X-Nanterre, but he’s originally from Arkansas and is staying with family members in Maryland for the summer. Although he studies languages in school, he loves biology and jumped at the chance to get out of the house while his hosts are at work during the day.

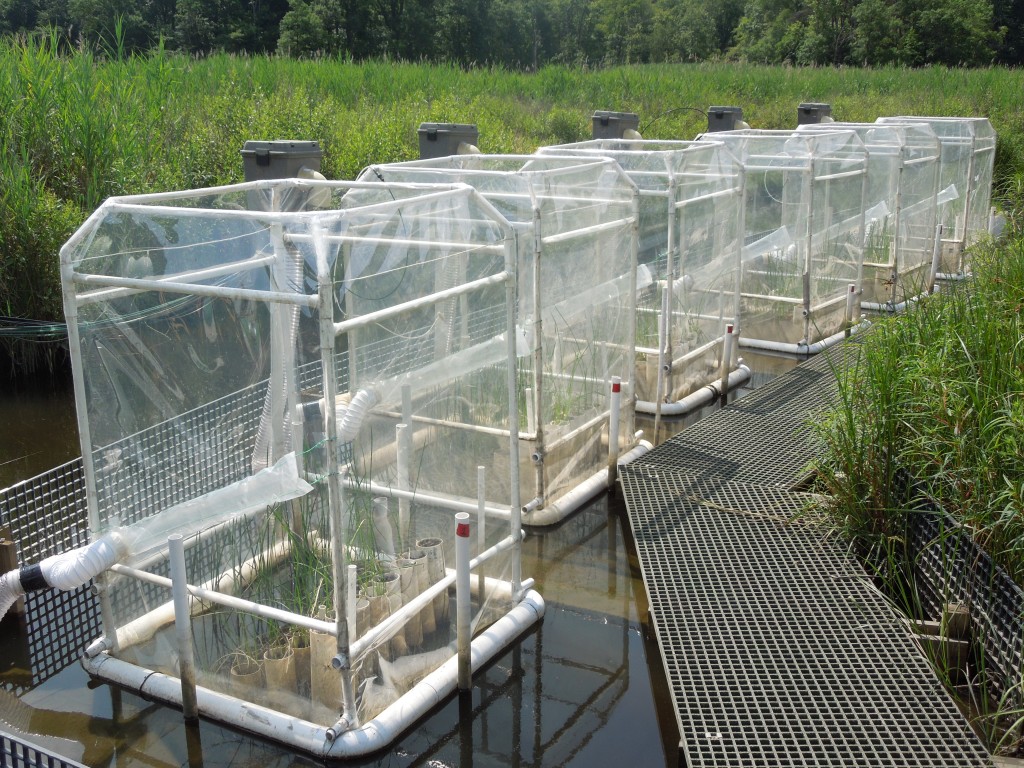

These chambers are part of the sea-level rise experiment at GCREW. The tubes of different heights model different levels of flooding.

While Downey is here to do something fun for the summer, Adam Langley has made wetland research his career. A former SERC postdoc, he’s now an assistant professor of biology at Villanova University who still does fieldwork at GCREW. The projects here are critical because “the way CO2 affects ecosystems is going to be determined by plants,” he said. He described another experiment at GCREW that models sea-level rise. In this case the marsh plants are growing in long cylindrical tubes arranged in staircase fashion, which tests how well plants grow with different amounts of flooding. By changing carbon dioxide and nitrogen in combination with sea level, SERC scientists are trying to understand how marshes will survive in a future world.

Rachel Gentile is a graduate student at the University of Notre Dame whose thesis project centers around data from the sea-level experiment, but today she’s counting sedges. “Everybody in the lab chips in a couple days for this,” she said.

Megonigal is thrilled because record numbers of volunteers are in the field this year, and the work is going faster than expected. His research goals expand well beyond the data-collection bonanza, though. Similar long-term studies are going on in a forest and an estuary at SERC. Megonigal said he and his colleagues are working “to get a whole landscape vision of productivity.”

Principal investigator (PI) Patrick Megonigal collects soil samples for a collaborator’s study at Rutgers University.

However, none of the research at GCREW would be possible without Gary Peresta, SERC environmental engineer. He’s been here since 1990, even before Megonigal. He started to list the equipment he’s responsible for: “62 blowers, 47 pumps, 5 data loggers, 2 stream gauges,” and then trailed off. “I don’t know….I wrote it all down once for fun.” He does seem to enjoy his job. He indicated the surrounding marsh, palms up, as a raptor dived into the stream and came out with a fish. “This is my office,” he said.

Megonigal, too, expressed gratitude for the opportunity to conduct wide-ranging research at this site. “This really is a unique place,” he said. Then he disappeared back into the sedge, zebra-patterned scarf protecting his neck from the sun, engulfed by plants and a robot-igloo.