by Dejeanne Doublet

As we’re knee-deep in the marsh surrounding the Chesapeake Bay, working under the relentless sun during 90-degree weather with 90 percent humidity, sweat dripping down our faces, waving off the summer bugs and trying to collect as much field data as possible, the idea of winter becomes abstract and far-fetched. It’s hard to believe we are out here in the blazing heat of summer studying the effects of this past winter— one of harshest winters this area has endured in many years.

While climate change has generally caused an increase in annual temperatures in most parts of the United States, including the east coast, scientists think that it is also likely to cause more drastic climate events in general, such as last year’s abnormally frigid winter.

The marshes around Chesapeake Bay were not immune to the impacts of a severe winter. For the plant species Iva frutescens, known by many as Marsh Elder, the freezing winter made for a tough several months that yielded some surprising responses by these plants along the Chesapeake watershed.

Iva is a distinctively woody shrub found in salt marshes along the east coast from Canada to Florida and along the Gulf Coast to Texas. According to current literature, Iva in New England generally grows in high marshes closer to solid land than to flooding zones. It is thought to have low tolerance to flooding, thus making its home at the landward edges of a marsh.

Marsh Elder, or Iva frutescens. Ecologists thought this plant struggled in flood-prone areas, but water may have saved it during the harsh winter. (Dejeanne Doublet)

However, Iva in marshes surrounding the Chesapeake Bay may not follow these rules. In fact, so far in our study, we’ve found more Iva growing along the lower and mid-marsh zones, where flooding occurs more often.

Not only are there more Iva in these lower zones, but it seems that the Iva growing in the lower zones may actually have endured this past winter’s freezing temperatures better than the Iva in higher zones. Which leaves ecologists with a burning question: Why?

The lower-zoned Iva may have survived better than the higher-zoned Iva because they are simply closer to the Bay water. To understand one hypothesis as to why this may be the case, we must think back to some basic elementary science.

Water has a much higher specific heat than air, which means that it takes more energy and time to raise the temperature of a body of water than it does to raise the temperature of the surrounding air. (It also takes longer for water to cool than it does for air.) Changes in water temperatures lag behind surrounding air temperatures. Because of this, you will find ocean water to be warmer than you may expect in the fall and cooler at the beginning of summer.

But bodies of water also have the ability to buffer nearby air temperatures, causing the air around them to heat and cool more slowly as well.

Iva in lower marsh zones closer to the water may have enjoyed this kind of thermal buffering this past winter, when overall temperatures fell below zero. That would explain why they are showing signs of better health than Iva growing in drier zones. If this is true, these results contradict current literature that describes Iva’s preferred habitat as being in low-flooded areas far from water, and could show how microclimates within habitats may buffer the effects of severe climate events, with sometimes surprising responses.

Tall plants could have the same effect. Iva found in areas where vegetation is denser and where surrounding vegetation is relatively taller may have fared better than Iva surrounded by fewer and shorter plants. We think Iva growing in a patch of tall plants, surrounding it and protecting it like a thermal blanket, may have survived more than lonely Iva that sticks out by itself, just as the proverbial tall poppy always seems to stick out like a sore (and in this case, cold) thumb!

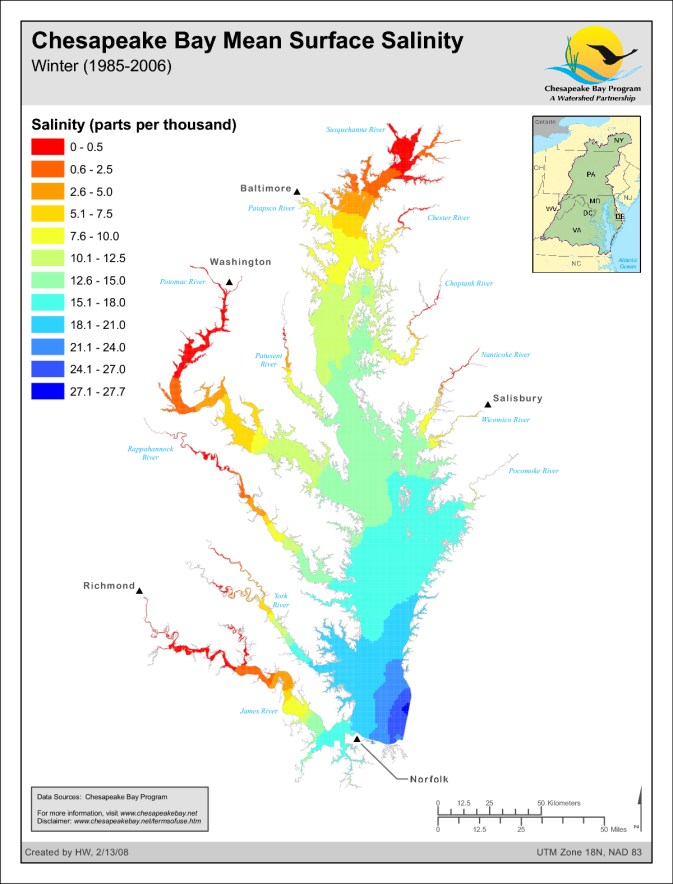

Along the Chesapeake Bay, another factor could come into play: salinity. The Bay has a salinity gradient from north to south, with salt water coming into the mouth of the Bay from the south and becoming fresher heading north. Salt water is more resistant to freezing than fresh water. For an ocean, the salt content translates to a lowered freezing point of about 2 degrees Celsius. This slightly decreased freezing point could mean that Iva growing in marshes near the south end of the Chesapeake Bay closer to the mouth may have had an advantage over Iva growing in marshes near the upper Bay.

Along the Chesapeake Bay, another factor could come into play: salinity. The Bay has a salinity gradient from north to south, with salt water coming into the mouth of the Bay from the south and becoming fresher heading north. Salt water is more resistant to freezing than fresh water. For an ocean, the salt content translates to a lowered freezing point of about 2 degrees Celsius. This slightly decreased freezing point could mean that Iva growing in marshes near the south end of the Chesapeake Bay closer to the mouth may have had an advantage over Iva growing in marshes near the upper Bay.

If this is true, this means that Iva could serve as an example of how increased drastic climate events caused by climate change could cause surprising responses by plants.

But before we can make any conclusions, we must first spend many more countless hours trekking through the thick marshes to collect more data.