by Kristen Minogue

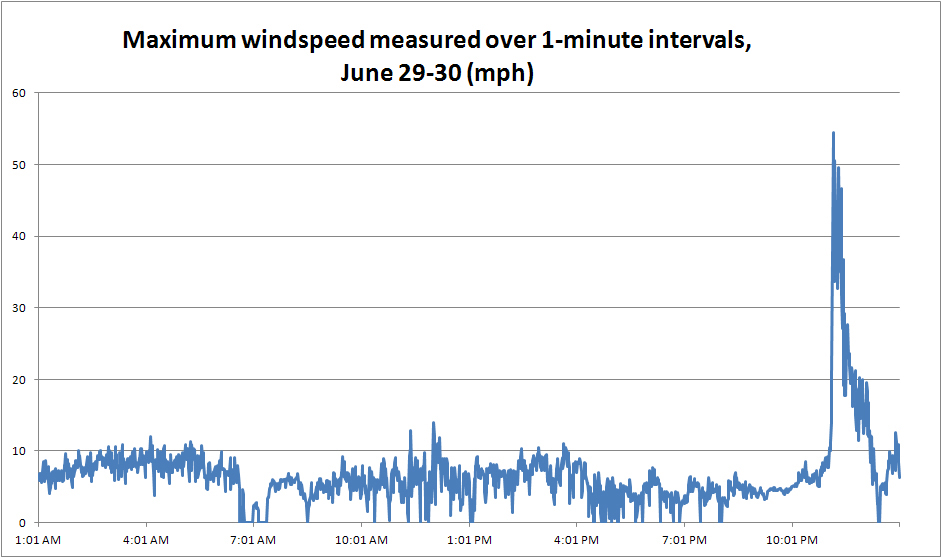

To say the tempests of June 29 took the U.S. by surprise would be an understatement. Near Annapolis, the storms jumped from a mild 10 miles per hour to 54 miles per hour in just five minutes. In other places 70- and 80-mile per hour winds tore through hulking trees and power lines. And yet the most violent part of the storm lasted less than half an hour.

“It all happened in a matter of minutes….I’ve never seen anything like it,” said ecologist Pat Neale, who tracked the wind speeds on SERC’s meteorological tower.

How could something so quick cause so much damage? And how would a storm like that form in the first place?

Media coverage brought the word derecho into the mainstream vocabulary. A derecho—also known as a “land hurricane”—needs three ingredients to take shape. All three were present Friday: a storm cluster, a strong wind and, most importantly, a massive supply of hot air.

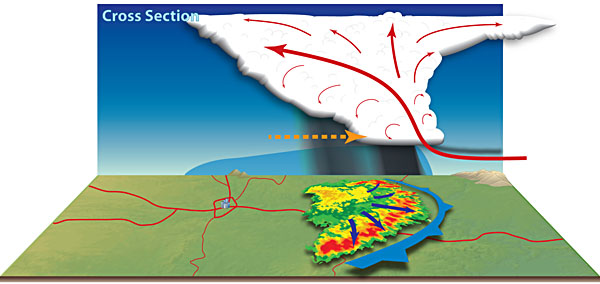

A derecho does not usually start as a single storm, but several that line up in a long, bow-shaped curve. That first set of thunderstorms sets the stage. In this case, the initial storms collected over northern Indiana Friday afternoon.

Over time, if a strong enough wind pushes them in one direction, the storms curve out into an elongated bow echo. This stretches the most violent area of the storm into a thin strip—never lasting very long in any one place, but able to leave a wide trail of destruction in its wake.

Bow echo. Rising warm air (red arrow), creates new thunderstorms with their own winds that push the storm system outward into a bow-shaped curve. (National Weather Service)

Warm, moist air rises easily. The cold air pushes the hot air upward, where it can then fuel more thunderstorms. These new thunderstorms add their own winds and downdrafts to the ones already in place, creating a vicious cycle of ever-rising intensity. In this case, the scorching air sustained the storm for 700 miles on its path from Indiana to the Atlantic Ocean.

Because they rely on heat, derechos are most common in late spring and early summer, with more than 75 percent emerging between April and August. In the mid-Atlantic derechos occur once every four years on average. They’re more common in the Midwest, where land hurricanes can be an annual affair.

More on the science of derechos >>

Windspeeds above Edgewater, Md., on June 29, 2012. Data from Smithsonian Environmental Research Center Meteorological Tower.

Top image of storm front available for reuse under Creative Commons license

Thank you! We were just discussing land hurricanes last week after the storm ripped through our neck of the woods (Maryland, near Annapolis).

A “land Hurricane” brings out the fear in mid-western residents and with this current string of hot seasons, I fear myself that we are going to be inundated with these strong storms.