by Tuck Hines

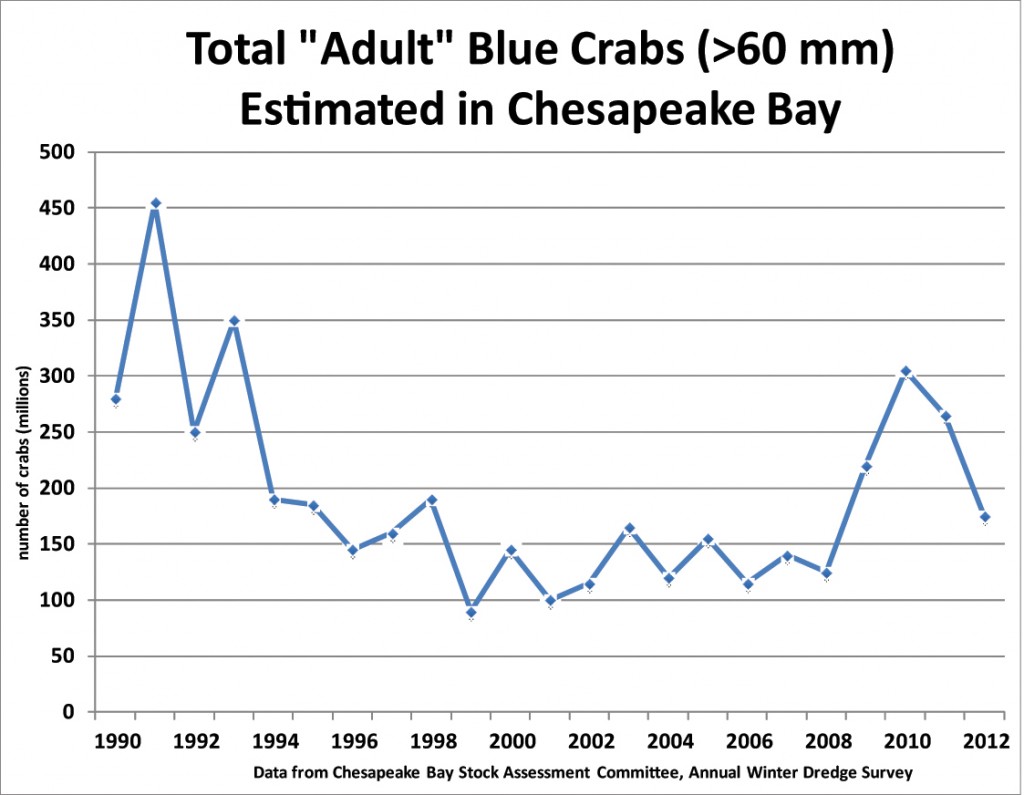

Few creatures in Chesapeake Bay have experienced the kind of whiplash felt by the blue crab. Having gone through a near-disastrous decline that lasted almost two decades, they made a dramatic comeback starting in 2009. But before managers could proclaim it a success, the numbers fell again. And this time, the reasons aren’t so clear.

The first drop began in the early 1990s. After 40 years of abundance, the Bay’s icon took a nosedive. By 2000 the number of mature females in the lower Bay spawning area fell 84 percent to a record low. Meanwhile, prices skyrocketed above $300 a bushel. To satisfy demand, the Chesapeake resorted to importing large quantities of crabs from other states and crab meat from related species in Southeast Asia.

Fortunately researchers at SERC and elsewhere have shown how sound science can advise policy and management. We have a tool to estimate crab abundance: the Winter Dredge Survey, which pulls dredges through the Bay’s bottom sediments at 1,500 random sites during cold months when crabs are buried. For almost 20 years the survey tracked a decline. Researchers at SERC and around the Bay indicated fishing was taking too many crabs, especially mature females. Female crabs comprised up to 80 percent of the Virginia catch and more than half of Maryland’s. Meanwhile, SERC research from 2000 to 2008 showed there were not enough baby crabs to replenish the fishery.

Finally in 2008—the year officials declared the fishery a federal disaster—Virginia imposed major restrictions on harvesting female crabs, and Maryland reduced the take of females migrating down the Bay. The population immediately rebounded in 2009 and 2010. The recovery demonstrated two things: First, political will to make real changes can produce results. Second, overfishing was the main cause of the decline, although other factors surely contributed.

But last year saw a twist. Adults dropped slightly in 2011 and more sharply in 2012, even though young crabs continued to increase. The decline hit females particularly hard. Fishery managers offered confusing explanations. They said the 2011 drop was due to winter mortality after an unusually cold December. SERC data show extreme winters do cause crab mortality, but only at temperatures below 3°C (37°F) combined with low salinities. That was not the case in 2011. Then managers attributed the 2012 decline to warm winter temperatures that allowed females to escape being caught by surveyors. But Bay water was well below 10°C (50°F) most of the winter—still too cold for crabs to avoid the dredge. And there are no indications female crabs were hiding somewhere not sampled by the survey.

What is going on? Perhaps female abundance did decline, caught by watermen who managed to get around the regulations. Perhaps offshore storms brought more larvae into the Bay. Or perhaps the dredge survey does not categorize crabs correctly, since it considers crabs larger than 60 mm (2.5 inches) adults, although many still have six to 12 months before reaching maturity. After 30-plus years studying blue crabs, I still seek answers.

Tuck Hines is a crab ecologist and director of the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center

how about seven billion of us?