by Heather Soulen, research technician

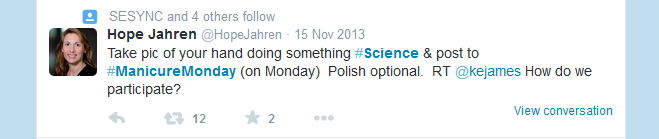

In mid-November of 2013, Seventeen Magazine’s #ManicureMonday was hijacked by Hope Jahren, an isotope geochemist and laboratory scientist studying photosynthesis at the University of Hawaii Manoa. She tweeted:

And then tweeted this picture of her well-groomed, unmanicured hands doing something #Science:

Jahren’s nails are much less adorned than the typical Seventeen Magazine #ManicureMonday nails. (Photo c/o Hope Jahren)

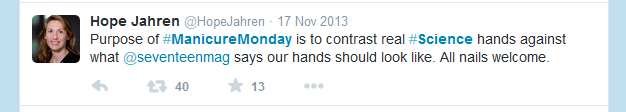

When following tweets asked “Why?” Jahren followed with:

Thus began an emotionally charged verbal tennis match about women in science, stereotypes, shaming, STEM and gender roles on Twitter and Reddit, as well as commentary featured in blogs like Slate Magazine, Scientific American and The Huffington Post.

While the #ManicureMonday #Science hijack seemed to begin with good intentions, it ultimately sparked controversy. But controversy is good–it makes us stop and think about our worldviews. It encouraged individuals to examine things like motivation, assumptions and perceptions of all kinds, including dichotomous thinking like “you can either be smart or manicured.”

There are plenty of scientists who enjoy adorning their fingers and toes with nail polish, but for many of us there is a practical reason we forego gilding. That is, doing some kinds of science simply destroys manicures and pedicures. Whether it’s from wearing nitrile (synthetic rubber) gloves all day, donning dive booties, deploying research gear (e.g. nets and samplers), scrambling around research boats, tromping around field sites (estuaries, streams, marshes and forests), or performing experiments in wet labs or outdoor mesocosms, hands and feet take a beating. Yet, we still use nail polish. We just use it in a different way.

Click to continue »