Food doesn’t typically get the spotlight in talks on climate change. Even when human health enters the picture, heat waves and category 5 hurricanes often dominate coverage. But as the Earth changes, so does agriculture. That raised just one of several questions scientists wrestled with at the Smithsonian’s second climate change symposium, titled “Living in the Anthropocene”: What will the world’s 7 billion people eat?

Wheat, rice, barley, potatoes and soybeans form staples in diets around the globe. But climate change is altering not just how well these plants grow, but their nutritional value, and not always in ways scientists expected. It’s a side effect of the Anthropocene, or “Age of Humans,” an unofficial title many have given to the last few centuries, when humanity has exercised unprecedented influence over the planet.

“Early on, there was kind of a rosy picture, that we would have longer growing seasons, warmer temperatures, and carbon fertilization,” said George Luber, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who opened the seminar on climate change and public health. Carbon fertilization—the idea that carbon dioxide can act as a fertilizer boosting plant growth—is more than an idealistic hope; it is an observed scientific reality.

“Carbon dioxide is an absolute essential to all life on Earth,” said Bert Drake, a plant physiologist from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) who spoke at the symposium. “When you give plants extra CO2, they grow better, and they use all of their resources more efficiently.”

The problem, however, is that CO2 is not the only thing changing. Plants also need water. And many parts of the world—including agricultural sweet spots like the southern U.S. and the Mediterranean—are expected to dry out. “If the Earth is drying out in certain regions where agriculture is required, then that can’t be a good thing,” Drake said.To continue feeding the world’s burgeoning population, crop productivity would need to increase roughly 2.4 percent per year, Drake said. Current estimates say yields from major crops like wheat and rice aren’t rising quickly enough to meet that demand.

More CO2, Less Protein

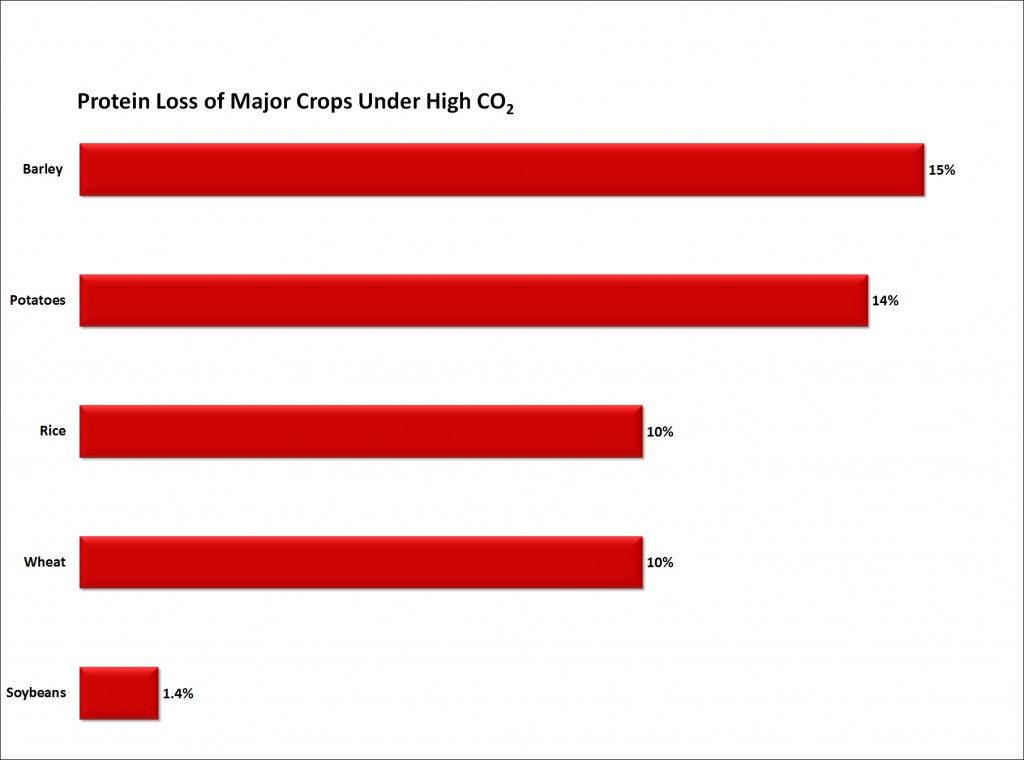

Another issue, which Luber pointed out: Even if plants grow more, will they be as healthy as before? The answer, according to an extensive combing through the research, is no. Staple crops grown under high CO2 have less protein, zinc and iron, sometimes up to 15 percent. “If we have a world of not 7 billion but 9 billion people, with 15 percent less nutritious foods, how do we solve that problem?” Luber asked.

The protein loss occurs because under higher CO2, plants lose less water from their leaves—and therefore absorb less water from the soil. The upshot is that they also absorb fewer nutrients from the soil, including nitrogen, which they need to make protein.

For Drake, the solution lies in finding ways to fast-track evolution. “Crop physiologists have got to figure out ways to adapt plants to this new atmosphere.”

Whitman Miller, a SERC marine biologist, had another suggestion: aquaculture. “We’re going to have to turn around and face the ocean,” he said. “I think that is where our food sources are going to come from.”

Aquaculture raises new questions of its own. Coastal waters, where many of the world’s fisheries thrive, face even more drastic changes than the open ocean. But many animals, having evolved under naturally fluctuating conditions in coastal oceans, may have a greater capacity to withstand the coming changes. Ultimately, planning the global menu for the next century may boil down to discovering which species—whether in land or water—are most resilient.

Data source: “Effects of elevated CO2 on crop protein concentration.” Global Change Biology, 2008.

Data source: “Effects of elevated CO2 on crop protein concentration.” Global Change Biology, 2008.